ON April 14, 1956, two young Irish men walked into the Tate Gallery in London with one brazen objective in mind – to seize an £8million impressionist masterpiece in the name of their country.

Dubliner Paul Hogan and his mate Billy Fogarty from Galway believed that the painting, Berthe Morisot's Jour d'Eté, was the property of Ireland and had been unjustly obtained by the British Government.

Hogan, then a 21-year-old art student, had used his status as an undergraduate to get close to the masterpiece.

He and Fogarty scoped out the joint for a number of days previously, pretending to sketch the numerous artworks as they instead learned when the guards took their morning tea breaks.

The pair hoped that when they were inevitably caught departing the gallery with the canvas underarm, that mass attention would be brought to their cause.

So confident were they that commotion would be created that they arranged for a press photographer to take a shot of the act.

Only, when they made it out of the museum’s front entrance without so much as an eyebrow being raised by a security guard, the dumbstruck duo had no idea what to do next.

A priceless masterpiece

Jour d'Eté, which translates as ‘Summer’s Day’, was worth £10,000 at the time and is now valued at around $10,000,000 (£8,000,000).

The painting was part of a priceless collection of 39 artworks known as the Hugh Lane collection.

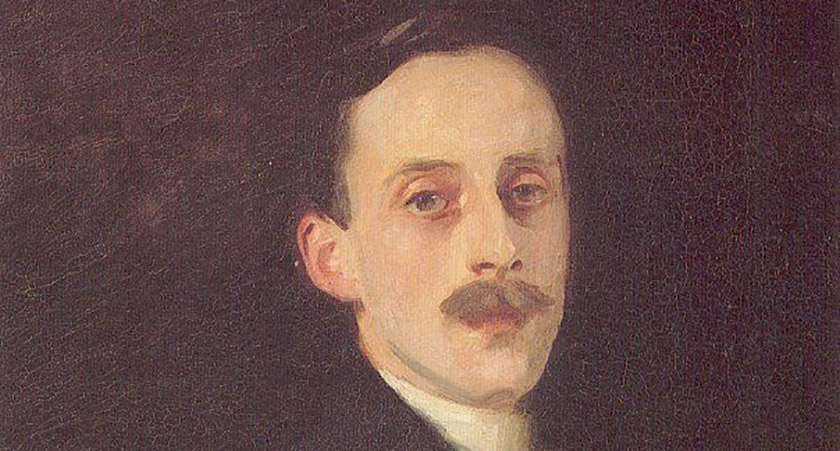

Sir Hugh Lane, an Irish art dealer, died aboard the Lusitania after it was infamously sunk off the coast of Cork by a German U-Boat in 1915.

Before his death, Mr Lane explicitly bequeathed his collection to the ‘people of Ireland’ in his will.

However, the document was not witnessed, and a previous clause promising the paintings to the Tate Gallery in London was enforced by Britain – generating yet another toxic bone of contention between the two nations.

The British authorities’ refusal to honour Lane’s last wishes was firmly in the minds of Hogan and Fogarty when, 41 years later, they decided to correct what they viewed as an ongoing injustice.

The ‘uncultured Irish'

It all sounds like something plucked straight out of the opening pages of a screenplay, and soon enough, it will be.

Two Irish filmmakers, Keith Farrell and Stephen Hogan, have toiled for years to give the heist its own big screen treatment.

A feature film, tentatively titled Taking the Picture, with a script written by Oscar-nominated filmmaker Michael Creagh, has already cast two actors in leading roles.

Farrell and Hogan have relentlessly researched the incident, and say that looking back, the arrogance of the British Government at the time was astounding.

"If you read the files from the time, they're very patronising towards Ireland – they actually say things like; 'while we recognise the Irish state has a moral right to the paintings, we don't believe the Irish are culturally aware enough to appreciate the works'”, Farrell said.

“Almost from the foundation of the Irish state, the Irish Government tried to get the Hugh Lane paintings returned to Dublin, but by the 1950s there was still no progress.

“It was this frustration with the British Government that was behind Paul Hogan and Billy Fogarty’s decision to seize one of them and return it home.”

That, and rock 'n' roll.

1957 was a time of incredible social transformation – James Dean’s seminal Rebel Without A Cause, the chagrin of many a parent of a rebellious teen – was released just two years previously in 1955.

If that wasn’t enough, Elvis Presley’s eponymous debut album came out the previous March, prompting thousands of young men to ditch tweed blazers for leather jackets, and to grease their hair in a triumphant middle finger to the establishment.

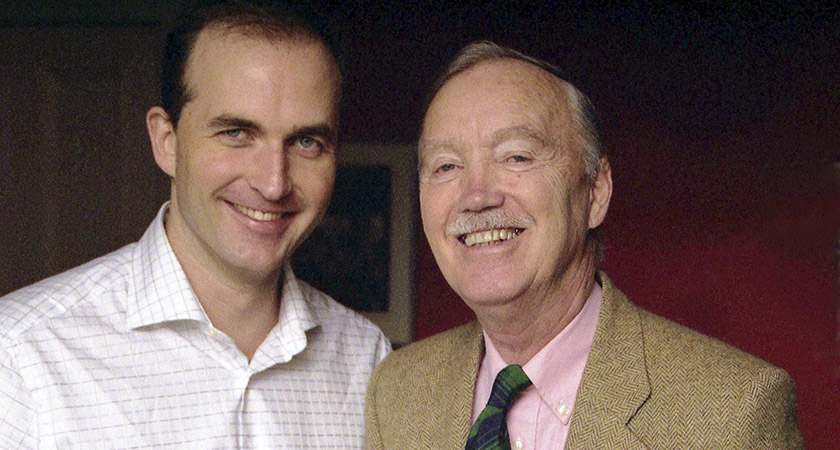

The Tate heist was firmly in keeping with this rebellious new tradition, says Stephen Hogan, who is the nephew of one of the protesters.

“This was a generation who were born in an independent Ireland and were just coming of age really, and there was a sense that direct action – student action – was what you did to change things,” Hogan said.

“The Suez Crisis was happening, rock ‘n’ roll had just come out, jazz was happening, rationing was over and people were beginning to breathe after the war.

“Young Irish people really felt that small acts could change the world, and my uncle’s take on that was to lift a painting off a wall.”

Taking the picture

When 21-year-old Paul Hogan descended the front steps of the Tate Gallery with Jour d'Eté under his arm, he was left puzzled by just how easy it had been to pinch a priceless masterpiece from under the noses of the guards.

He wasn’t perplexed for long though, as the flash of a nearby camera brought him firmly back to the task at hand.

Hogan and Fogarty, who planned the heist for some time, were startled by the appearance of the photographer they had booked to document their act of political protest.

“The photographer was supposed to capture the moment Hogan and Fogarty got into fisticuffs with the security guards in the revolving doors, get the picture, and hit the headlines,” says Stephen.

“The photographer was standing around waiting and waiting and there were no students coming out.

“Suddenly, my uncle comes rushing down the stairs with a huge painting under his arm and behind him, his mate Billy shouts with an Irish accent ‘take the picture’, and the photo which went around the world was born.”

The Irish students, unfamiliar with London, now had to decide upon their next move. They got into a black cab and asked to be taken to the first place that came to mind – Piccadilly Circus.

Meanwhile, the press photographer who captured their audacious act was having his photograph developed, and the next morning it would hit the front pages.

A wild goose chase

Hogan had chanced on a meeting with an Irish woman in a bar the night before, and the pair quickly headed to her flat with nowhere else coming to mind.

The Irish woman, Mary, agreed to let them hide the artwork under her bed. The men could relax, but not for long.

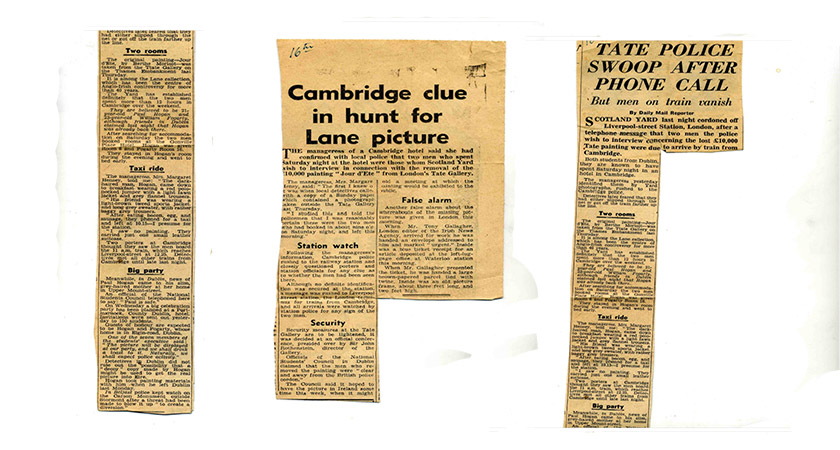

The photograph of Paul escaping the gallery with the painting under his arm was published in newspapers around the world and the Metropolitan Police were soon hot on their tail.

The officer in charge of the investigation was one DCI McGrath. The Dubliner was in demand after he solved the case of the missing Stone of Scone in 1950.

In a remarkably similar circumstance, the Stone of Scone had been stolen by four Glaswegian students intent on reawakening a sense of national identity amongst the Scottish people.

DCI McGrath had solved that case and he was determined to locate the Jour d'Eté, too.

“It was a case of an Irishman hunting Irishmen,” says Farrell.

Mission successful: The painting was returned to the Tate but the collection was soon shared with Dublin.

Mission successful: The painting was returned to the Tate but the collection was soon shared with Dublin.It was quickly discovered that the suspect in the photograph was the son of a senior civil servant in Ireland, and a spotlight was soon on Paul Hogan’s family.

“When it was found that he was the son of Sarsfield Hogan, a senior adviser to Taoiseach de Valera, all hell broke loose,” Farrell added.

“The family had the press knocking on the door and suddenly young Paul was the big fugitive of the time.”

Hogan and Fogarty, who had taken to disguising themselves as priests to escape the authorities in Cambridge, eventually decided to ask Mary to return the painting to the Irish Embassy in London.

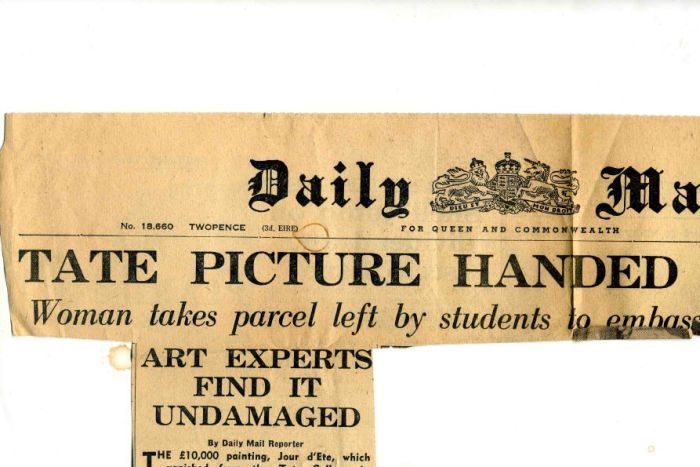

She agreed and the painting was quickly returned to the Tate Gallery.

But their escapade was not in vain, as the Tate eventually agreed to share the paintings with Dublin, while controversially retaining ownership.

DCI McGrath, who discovered that the pair were making a run for the Liverpool ferry, called up the Hogan household and told Paul’s mother that he was letting them go.

“They got off the ferry and Paul’s mammy was waiting in the car. The only thing she said was ‘get in the car’, and that was that,” adds Farrell.

The man himself: Paul Hogan (right) with his nephew, Irish actor Stephen Hogan. Picture: Hogan family

The man himself: Paul Hogan (right) with his nephew, Irish actor Stephen Hogan. Picture: Hogan familyOngoing injustice

The Hugh Lane collection remains under British ownership to this day, but the current sharing arrangement with Dublin ends in 2019 and it is hoped that the paintings can be returned to Ireland thereafter.

Keith Farrell and Stephen Hogan say that their film, which they hope can come out in 2019 to coincide with the end of the arrangement, could tip the balance.

Fionn O’Shea (The Siege of Jadotville/Handsome Devil) has been cast in the role of Paul, while actress Sarah Greene (Penny Dreadful/Vikings/The Guard) has landed the role of Mary.

“The story of the Hugh Lane collection is far from over, but hopefully soon my uncle can see his wish come true after 60 years,” says Stephen Hogan.

“It’s about time.”