HAVING served as Irish Ambassador in London and Washington, and lived for some years in Australia, I have acquired an active interest in our global diaspora.

On a recent visit to South America, I made contact with the Hurling Club of Buenos Aires and with the editor of the Southern Cross newspaper to get a sense of that lesser-known part of Ireland’s diverse diaspora.

Silvia Fleming from the Hurling Club told me about the club’s history, stretching back to its foundation in 1922 by Irish immigrants and their descendants, who came mainly from counties Longford, Offaly and Westmeath.

Hurling and Gaelic football are still played at the club alongside rugby and hockey.

Silvia’s heritage is heavily Irish, but her nearest Irish-born relatives were two of her great-grandparents who arrived in Argentina in the late 19th century. Yet she retains a strong affinity with Ireland.

Guillermo McLoughlin of the Southern Cross newspaper is proud of his paper’s pedigree as the oldest English language publication in Latin America.

It was founded in 1875 by an Irish priest and politician, Monsignor Patrick Dillon.

The paper’s best-known editor was William Bulfin, who emigrated to Argentina in the 1880s, but returned in 1902 for a cycling tour of his homeland.

He wrote down his impressions for the benefit of Irish exiles in Argentina and they were subsequently published as Rambles in Eireann, which has just been re-issued in a handsome edition by Irish Academic Press.

Bulfin, a fervent turn-of-the-century nationalist and a close friend of Arthur Griffith’s, described his first glimpse of Ireland, from the deck of his steamer, an experience that will be familiar to the Irish in Britain who have travelled home by sea.

There was a faint bluish something at first, on the horizon which might be a flake of cloud; but little by little it rose into the sky and changed from blue to purple, and we knew that we were looking at the hills of Dublin....earth and air and sea were flooded with morning gold.

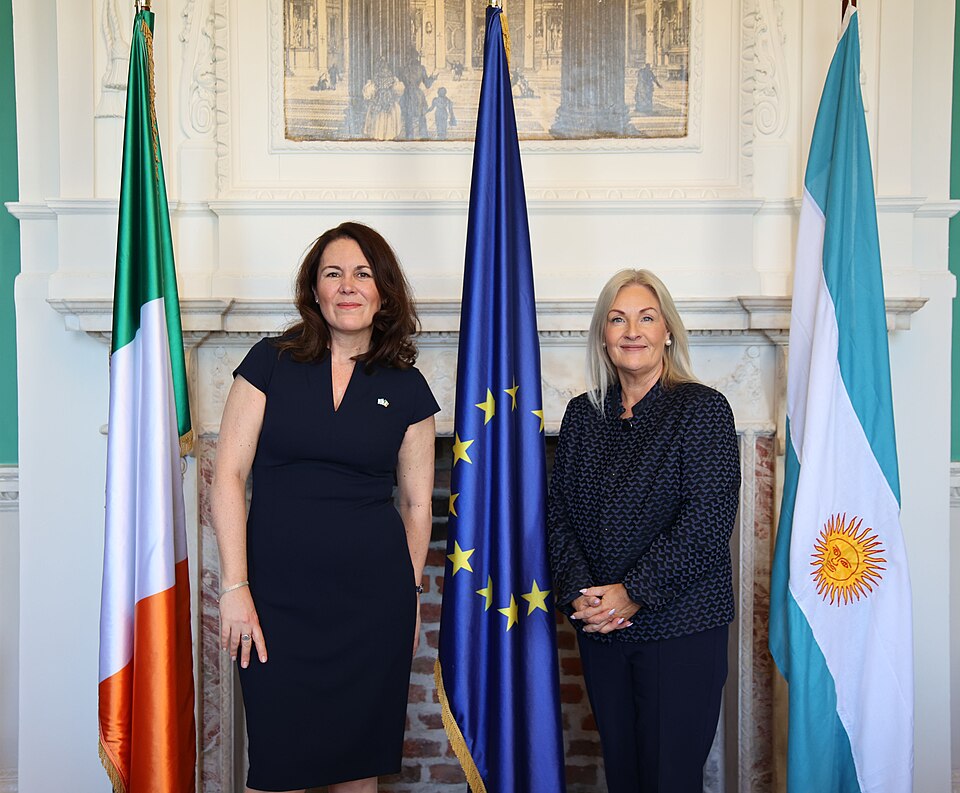

Ambassador Cachaza of the Argentine Republic pictured with Ceann Comhairle Verona Murphy

Ambassador Cachaza of the Argentine Republic pictured with Ceann Comhairle Verona MurphyRead through a 21st century lens, Bulfin’s evocations of Ireland are endearingly sentimental. He depicted Ireland as a beautiful fairyland and relished ‘the perfumed winds of an Irish summer’. He even had respect for Ireland’s rain, which was, he wrote, ‘a kind of damp poem’. You get the idea.

The diversity of our diaspora was brought home to me again at the recent Annual Congress of Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann in Sligo. As you can imagine, that weekend gathering was replete with exceptional traditional music.

At the opening session there was a performance by a group that included Birmingham’s Vince Jordan, as well as musicians from the USA and Canada, plus three from Brazil. Comhaltas has been a huge success story and now has branches in 22 countries including Japan and Korea.

I took part in a panel discussion on the Irish diaspora, which I see as a huge asset for Ireland, but one that needs to be nurtured.

Historically, the overseas Irish played a big part in Ireland’s politics.

The role of the Irish in America in support of the nationalist cause is illustrated by the fact that four of the seven signatories of the 1916 Proclamation had either lived in or visited the USA.

The Irish in America came into their own most recently in helping Ireland manage the fall-out from Brexit.

Ireland’s freedom struggle had an important support base in Britain too, something I have written about in an Irish Post review of Darragh Gannon’s Conflict, Diaspora and Empire: Irish Nationalism in Britain, 1912-1922.

Ireland has moved on a lot since those days and so has our diaspora, becoming more successful in their adopted homelands and more ancestrally-distant from Ireland.

With the drying up of mass emigration from Ireland, the number of people of recent Irish descent living overseas is likely to decline and the nature of their attachment to Ireland may well change.

There may be times in the future when Ireland will need the support of ‘her exiled children’ as the diaspora was described in the 1916 Proclamation, but Irishness is far more than a political condition composed of aspiration and agitation.

Its cultural dimension seems set to be more important as the experience of mass emigration recedes in time.

I have seen enough of the Irish world outside Ireland to know how important the GAA, Irish dancing and traditional music are as pillars of identity.

I have often heard people of Irish descent in Britain and America complain about being told in Ireland that ‘you’re not Irish’. We need to move past the idea that Irishness is synonymous with birth in Ireland.

There are those in Ireland who want to define our identity narrowly, even xenophobically.

That would deprive us of a precious asset that underpins Ireland’s possession of international influence through the heel of a dancing shoe and the neck of a fiddle. We ought to cherish the kind of ‘broad church’ concept of Irish identity that I have seen on display at the Hurling Club in Buenos Aires and at the Comhaltas Congress in Sligo.

Daniel Mulhall is a retired Irish Ambassador (who has served in London and Washington), a consultant and an author. His latest publication is Pilgrim Soul: W.B. Yeats and the Ireland of his Time (New Island Books, 2023). He can be followed on X: @DanMulhall and Bluesky: @danmulhall.bsky.social.