FORMER Arlington House resident and later manager, Joe McGarry passed away this month.

He left Northern Ireland in the 1970s and found work in London’s Camden Town, where he spent many years battling alcoholism as a long-term resident in the Arlington House wet hostel.

Despite his challenges he went on to make a miraculous transition and lived a life in sobriety for many years that was full of achievements and adventure.

Here his long-term friend and former colleague Alex McDonnell remembers a man who never ceased to impress everyone around him…

"I saw Joe before I met him on the Channel 4 documentary ‘What Do You Want Paradise?’ which was screened in 1993.

He appeared in another documentary shot in the House during the refurbishment called ‘Men of Arlington’, he was also photographed for the ground-breaking novel of emigration, I Could Read The Sky and in Deirdre O’Callaghan’s photographic study of Arlington called, Hide That Can.

I was immediately drawn to this articulate and charismatic man who talked about emigration, homelessness, and his relationship with alcohol with honesty and candour.

I also learnt a lot about this amazing building in Camden Town, which as Joe said had housed more Irish men than any other, outside of prison, anywhere in the world.

At that time, it was the only ‘wet’ hostel in London, where people could drink alcohol in designated areas.

There were 450 (1400 in earlier years) men in the house and half of them were Irish.

At that time, it was estimated by homeless charities Shelter and the Simon Community that between 30 and 40 per cent of all the street homeless in London were Irish.

Joe McGarry, right, with the Aisling Project's John McGlynn and Mary Leyne at the charity's fundraising event held at Kempton Racecourse in 2021

Joe McGarry, right, with the Aisling Project's John McGlynn and Mary Leyne at the charity's fundraising event held at Kempton Racecourse in 2021These were the days of cardboard cities in the Bullring at Waterloo and the gardens in Lincolns Inn and when patrons of the opera complained about having to step over homeless people on the way to the theatre.

A couple of months after seeing the documentary I got a job as Irish Support Worker in Arlington and I went looking for Joe who at that time had moved into a flat in SE London after rehab with the Drink Crisis Centre.

He still visited Arlington and he chaired our Irish Tenants Association.

I was secretary and between us we tried to keep some kind of order.

A typical comment from the floor was, ‘Look at McGarry with a pen in his hand. I remember when he only ever had a can there’.

Prophetic words from Timmy Buckley. One day I received a call from Joe in crisis, ‘I need to book back into Arlington’.

I drove out to Brockley to pick him up. He had broken out on the drink and he slammed the door on his flat without a backward glance.

I had managed to get a few cans of Red Stripe lager from a West Indian takeaway on the journey over to temper Joe’s withdrawals.

Joe sat in the van on the way back to Camden and downed the first one in a single swallow, wound down the window, crushed the can in his hand and tossed it right across the New Cross Road into a waste bin at a bus shelter as we were driving past.

‘Did I ever tell you I was all Antrim darts champion?’ he said nonchalantly.

There were many sides to Joe.

Myself and two other Irish community workers John Glynn and Deirdre Robinson recognised that thousands of Irish people were hiding away in places like Arlington House and on the streets.

We set up the Aisling Project to get people home to Ireland for a break and also to break the cycle of shame and pride that kept so many of them in exile for so long.

Joe had many goes at kicking the drink, but none stuck until we took him on one of the Aisling trips to Bundoran in Donegal.

Joe had some sort of revelation during that week that he couldn’t carry on with this crazy life any longer.

It was one thing to drink chaotically in anonymity in the drinking room in Arlington House but he couldn’t face doing the same in his home country.

Joe McGarry was on the board of the housing association Novas

Joe McGarry was on the board of the housing association NovasOne of the things that struck Joe when he sobered up in Donegal was that his usually immaculate hair was a mess and yet he was reluctant to buy a comb.

He had one back in London and the drinker’s mentality told him it was waste of a pound that could be spent on drink, but he did buy that comb and learned one of many lessons that helped him through sobriety.

Over the years that followed Joe had many such revelations and he told me he was amazed at the clarity that increasingly came to him as each sober day passed.

He was a life-long learner and loved to discuss ideas and if he read or heard something that he found interesting Joe would write it on the door of the wardrobe in his room and after a while both sides of the door were covered in words and phrases.

He became active in the Arlington Tenants Association and was invited onto the board of Novas, the housing association that managed the house and many others.

People recognised Joe’s intelligence and charm and soon he was made chair of the whole organisation and eventually he was to become manager of Arlington, the hostel he had lived in for so many years, overseeing a major refurbishment in 2005, it’s centenary year.

Joe’s ability to take on challenges was again tested when a delegation from Limerick came to London to see the famous wet hostel in Camden Town.

There was a major homelessness problem in Limerick and none of the hostels or shelters would take anyone in who drank alcohol.

As we had seen in London this condemned many to life on the streets.

The council was determined to do something about this, and Joe, as always, rose to the challenge and headed for the west of Ireland.

There was no budget, so first of all Joe took over a derelict fire station in the city centre and got some beds that the health board were getting rid of.

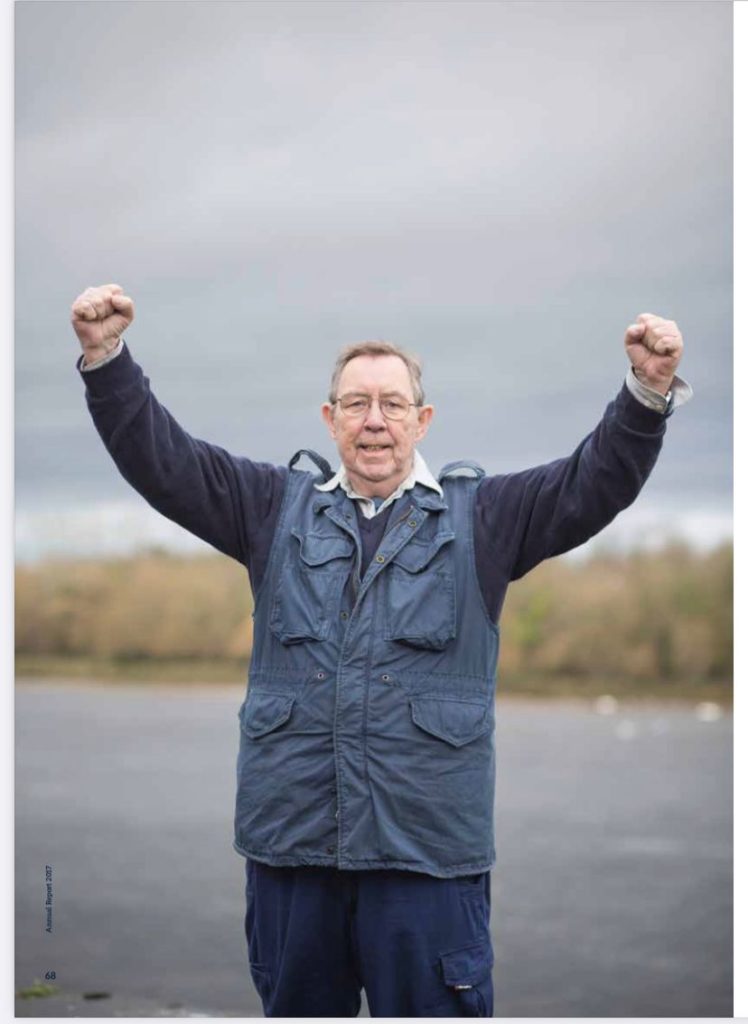

Joe McGarry won his battle with alcoholism and went on to live his life to the full

Joe McGarry won his battle with alcoholism and went on to live his life to the fullHe begged and borrowed whatever equipment he needed and opened the doors to every homeless person in the city.

Eventually they were able to move into better accommodation, which is now called McGarry House, as well as several more properties across Limerick.

He set up similar projects in Kerry and Tipperary, where he and a local nun survived a fire-bomb attack by ‘NIMBYs’ in Thurles who didn’t appreciate resources going to homeless people.

It had long been an ambition of Joe to visit Australia, which is where he met Mary the love of his life.

They were married in Camden Town registry office, and he returned with her to Australia on another adventure where he found yet more use for his talents in Sydney - where Joe worked for 10 years in the detox unit of St. Vincent’s hospital.

No better man for the job.

Back in Ireland Joe and Mary made a home in Celbridge, Co. Kildare and he continued to work with Novas Ireland and Aisling, helping Aisling to set up a housing association to acquire a home for returning emigrants.

During the last two Covid years Joe found a new interest in attending online AA meetings. He said he met so many inspirational, intelligent people from all around the world with fascinating stories to tell.

Of course, so did they."

Alex McDonnell is the founder and co-ordinator of the Aisling Return to Ireland Project - of which Mr McGarry was a committed team member. For further information click here.