In An Undistinguished Boy Paul Clancy elevates the small dramas of childhood against a backdrop of 20th-century upheaval. MAL ROGERS reports

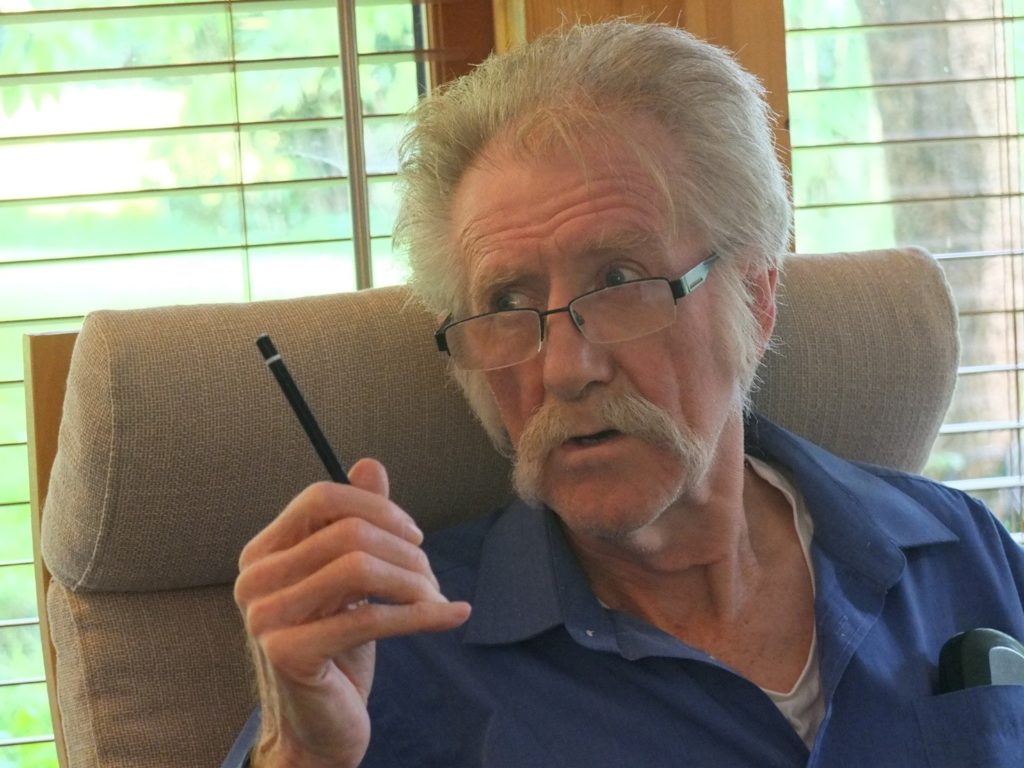

The author Paul Clancy

The author Paul ClancySOME memoirs are about presidents, popes, prize-winning poets. Sportspeople, actors, pop stars figure high as well.

But other memoirs are about the rest of us. In the right hands these can be far more entertaining, and of course in many ways a truer reflection of the times being lived through.

An Undistinguished Boy bills itself, with modesty, as “a minor life during major events”. It’s an apt subtitle, but also a sly understatement. This is a memoir that might not feature epic battles or world-shaking decisions, but it offers something else: the wry, exact recall of a boyhood spent in post-war Dublin. This is filtered through an adult sensibility that prizes the absurd and, possibly unusually for an Irish book, forgoes the temptation to romanticise the past.

FROM the opening pages, the author Paul Clancy frames his life against a backdrop of history. And this is a momentous century, let us not forget (although the acerbic Clancy would probably hint that every century is momentous).

But throughout the book, we readers are given the background to world-shaking events.

“The atomic bomb is tested; Leo Fender develops the electric guitar, the Iron Curtain is welded shut …"

(That ‘welded shut’ is masterly. I’ve read about the Iron Curtain coming down, descending, going up etc — but never ‘welded shut’. That is a totally apt description.)

Clancy continues: ". . . . the Soviet Union wins the Space Race; teenagers are invented; the Suez Canal is closed.”

Into this parade of epochal moments the author slips his own modest counterpoint: “Puberty hits; and through all of these the author drifts, blithely oblivious to everything… except puberty.”

The juxtaposition is more than a gag — it’s the book’s structural conceit, using the contrast between the seismic and the small-scale to illuminate both.

The first story sets the tone. In the summer of 1947, the four-year-old Clancy sees a girl: “six years old and on her way home from school”, and decides to act. In his “first conscious foray into crime,” he pulls up a forbidden handful of Michaelmas daisies from the back garden and wordlessly hands them over. The result is brutal: “The purplish flowers lay bent and broken in the dusty gutter. Something awful happened inside me; my guts turned upside-down and seemed to dissolve into slime, as ice formed around my heart.”

That sense of melodrama, laced with humour and sometimes pathos, runs through the whole book.

Paul and Anne

Paul and AnneFamily members are painted with economy and wit. The mother, Kathleen Ryan, is the eldest of eight and a physicist by training — though, in 1930s Ireland, her degree couldn’t survive marriage. She “would turn off the heat on a cooker hob, just before a pan came to the boil, muttering things about latent heat”, a line that both sketches her character and hints at the social constraints that forced her from science into domesticity.

The father, Gerard Edward Clancy, is a bank man and a golfer, sometimes a pianist, and during 'The Emergency' (World War II) a nocturnal submarine spotter along the Clontarf seafront. This last role is delivered with a perfect deadpan: “He never said what he was supposed to do if he encountered Wehrmacht Storm Troopers establishing beachheads at the Yacht Club as he was poorly equipped to defend the Republic.”

The memoir’s eye for historical texture is sharp but unpretentious. We meet the strange, almost unique figure of the “Glimmer Man,” prowling kitchens in wartime Dublin to catch households using illicit low flames to eke out their gas rations. We learn that burglars went “straight for the gas-meter as the readiest, possibly the only, source of cash” and that in the 1950s “there was just no litter because packaging had not been invented.” This is history not as lecture but as remembered life

A leitmotif in the book is the “Boring Bloke in a Pub” (BBiP), a kind of footnote-as-character who pops up to offer semi-relevant facts before being told to pipe down. After a digression on latent heat, BBiP launches into an earnest explanation of “latent heat of fusion… and latent heat of vaporization,” only to be cut off with “That will be quite enough, thank you.” It’s a risky device, but here it works, partly because it mirrors the rhythms of actual pub conversation and partly as it allows the author to smuggle in factual titbits without breaking the memoir’s easy flow.

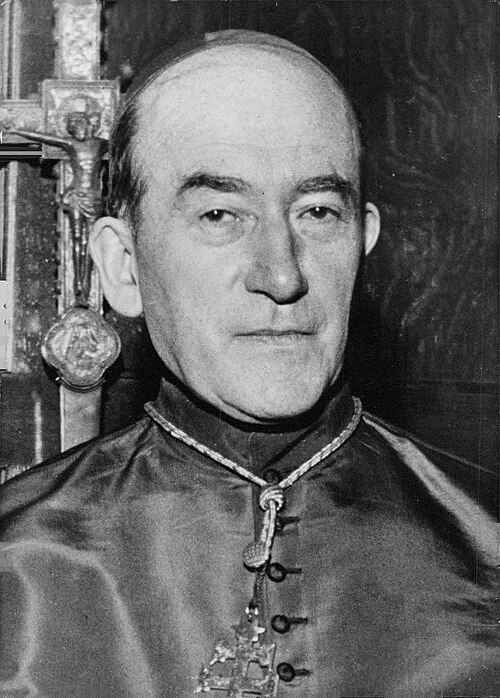

History and personal narrative weave together in more serious moments too. The 1941 bombing of Dublin’s North Strand is mentioned in passing, less for its geopolitical implications than for its unintended effect: causing his mother to go into early labour with his sister Anne. The creation of the State of Israel in 1948, Archbishop McQuaid’s fundraising for Italian Catholics, the introduction of myxomatosis to control Ireland’s rabbit population — all find their place here, refracted through the lens of someone whose life continued quietly alongside them.

The author with his accordion

The author with his accordionAnd yet, for all the big events that march through the background, An Undistinguished Boy never loses its focus on the personal. School, in particular, looms large. He recalls his first day at Belgrove National School, plunged into a holding pen of “traumatised children” and discovering that he must answer to the Irish form of his name, Pól. A fellow pupil’s tearful refrain — “Ah wanga guster!” — becomes a mini farce of misinterpretation until it’s discovered he wants his brother. There’s genuine affection in these portraits, but also a refusal to airbrush the noise, confusion, and low-level dread of early education.

Clancy also has a knack for a seemingly throwaway detail that lodges in the mind. Days of the week and months of the year have colours to him: Monday is “glowing green,” March “a cold pink,” April “a cold blue, like Antarctica.” Old radios still carried “tiny people… playing tiny instruments” in the imagination of the young. And the simple act of being given a lift to school on a milk cart — “Surrounded by metal churns… the noise deafening” — is rendered as vividly as any major set-piece.

There is a tenderness beneath the jokes, especially when touching on family bonds. His father’s friendship with “Uncle Hugh”, not a relative, but godfather to his sister, brings in stories of music, Christmas traditions, and a shared pleasure in small luxuries. The reader senses that, for all the teasing asides and mockery of his younger self, the author’s memories are stitched together by loyalty and affection.

Another bit player in Paul Clancy's story — Archbishop John Charles McQuaid (public domain)

Another bit player in Paul Clancy's story — Archbishop John Charles McQuaid (public domain)The cast of characters

DOMESTIC staff make memorable appearances in the book. Annie, a housemaid from Cavan. The opening description of this woman is reminiscent of the writing of Patrick McCabe. She made a deep impression, it would seem, on the young Clancy. “During this time, we acquired a housemaid, or maybe we always had her. She was Annie, from county Cavan, and never had a surname. She sang almost all the time, though probably not when my parents were within earshot.

"She had one song, a traditional Irish or Scottish one, that buried itself deep in my psyche, and became the soundtrack to my childhood:

“I know where I'm goin'

I know who's goin' with me.

The Lord knows who I love,

But the De'il knows who I'll marry”

The lyrics are followed by the magnificent lines: “Annie told me that rain, of which we saw a great deal, was the tears of the angels in Heaven weeping over my misdeeds, which, as we now know, is not the case. She predicted a dire future, and a worse eternity, for me. “

Annie borrows the young Paul’s cherished blue-and-white paper flag for a Croke Park match, returning it ruined with an implausible tale of an ink-throwing rival supporter. “Who brings ink to a football match?” he asks, still indignant decades later. Her successor, Rita from Co. Louth, arrives courtesy of a family habit of “buying their servants in bulk, when they found a good source".

The author has a gift for spinning out the implications of such moments, letting them resonate, but never belabouring a point. His suspicion of Annie’s football-match story, for instance, feeds into a broader wariness about women’s guile. His childhood heartbreak over the Michaelmas daisies becomes, in retrospect, “a pattern for future relationships, and difficulties with older women”. This self-deprecation is genuine, but it’s also a narrative strategy, making the reader an accomplice in his own retrospective ribbing.

CHILDHOOD episodes themselves are gems of observation, comic and occasionally profound. Sent at age five to buy bread, Paul successfully navigates the trip to Kennedy’s Bakery in Killester. That is until confronted with an unexpected price increase of a farthing. Forced to return home for the extra coin, he suffers the assistants’ mockery on his second attempt: “‘Win the Sweep, did ye?’ They leaned against each other, quivering in helpless mirth.” The walk home is long enough for temptation to strike: “The curved golden-blond crust… its sides… pliant, palely waiting to be ravished.” By the time tea arrives, the loaf’s interior is a hollowed-out ruin.

A visit to a wealthy friend’s Georgian country house, The Donahies in Raheny, reveals the wonders of a ha-ha (“a stone-faced, hidden ditch… deep enough to prevent livestock climbing out”), an oratory (“you could pray in your pyjamas”), and an endless supply of Kennedy’s Christmas cake.

Wartime blackout leads to the discovery that Dublin had “one gasmask for the entire family,” which he tried on for fun, finding it “very uncomfortable, smelt funny, and the clear plastic visor used to fog up within seconds”.

Perhaps the book’s most impressive quality is its ability to sustain a consistent voice, sometimes comic, sometimes incisive, sometimes reflective, without ever feeling forced. The humour is observational rather than punchline-driven, the kind that makes you nod in recognition before you smile, sometime laugh. It’s there in the description of trams (“rattled like hell and always felt wonderfully unstable on curves”), in historical asides (“India is split; there’ll be trouble over that”), and in the constant small negotiations of family life.

Even when the subject matter is potentially grim — the slaughter of diseased hens with a two wood golf club, the dreaded tonsillectomy — the telling is handled with such a light touch that the reader is carried along without discomfort. That’s no small feat, and it speaks to the control with which the author balances tone.

In the end, An Undistinguished Boy isn’t undistinguished at all. It’s a beautifully shaped memoir of an ordinary Dublin boyhood, told with a precision and humour that elevate the everyday into something quietly universal. The history is accurate without being heavy, the anecdotes are vivid without self-indulgence, and that dry voice — mocking, affectionate, funny — is a constant pleasure to spend time with.

For anyone who lived through even part of the same era, the book will spark waves of recognition. For those who didn’t, it offers an intimate passport to a time and place that feels both familiar and long vanished. In either case, it’s a joy.

Witty, richly detailed, and irresistibly humane, An Undistinguished Boy proves that so-called “minor lives” can make for major reading.

An Undistinguished Boy is available at HERE