Following the launch of the Philomena Project, a call on the Irish Government to release thousands of forced adoption files, The Irish Post shines a light on victims of the shocking practice in Britain.

A BRADFORD man separated from his family in a home for unmarried mums has made an emotional plea to his long lost brother.

Fred O’Donnell was kept from ever meeting his relatives as a result of Ireland’s callous policy of giving away the children of single women.

But now the 76-year-old father-of-three faces a race against time to find his only living family after learning of his brother’s existence just last year.

“It would mean everything to me if I could meet him,” Mr O’Donnell said.

“That would be the most important thing in my whole life because every single day I have asked myself whether I have anybody in this world who is my own. I have gone through life thinking I have nobody who belongs to me.”

Irish social services have told the retired gas fitter that his brother is living in England. But they refuse to give him any more information because of privacy laws.

“I cannot understand that,” Mr O’Donnell said.

“The Irish Government should tell me because I am his next of kin and there are only the two of us. They should tell us how to find our relatives before it is too late because of everything we went through."

Although it would not assist his search, he added that he backs The Philomena Project.

The campaign, which launched last month and takes its name from the Hertfordshire-based woman whose story was made into Oscar-nominated film Philomena, aims to pressure the Irish Government into releasing 60,000 secret adoption files.

Campaigners claim as many as 85 per cent of the adoptions were forced upon unwilling mothers.

They say the files could help reunite children with their natural mothers, thousands of whom are believed to have fled to Britain.

Mr O’Donnell, who came to England in 1960, said the Irish Government should also compensate those who passed through mother and baby homes because of the suffering it caused them.

Up until last year, Mr O’Donnell knew nothing about his natural family except that his mum’s name was Julia.

He said he was passed between a series of “owners”, including orphanages, foster parents and cruel Christian Brothers, after being born in St Patrick’s Mother and Baby Home in Dublin.

“The Christian Brothers school was a very hard, tough place to be,” he said. “I got beatings and stuff like that from the Brothers and if you reported anything to a superior Brother you got double the beating.

“That was a terrible place and I never even knew why I was there until I got my records, which say I was sentenced to spend eight years there after being found begging in the streets.”

Fred visited his mother's grave in Cork last year

Fred visited his mother's grave in Cork last yearMr O’Donnell said he was never able to find out anything else about his mum.

But after his eldest daughter Theresa got in touch with dozens of organisations in Ireland, he finally discovered his roots and learnt that his mum had another son in a different mother and baby home two years before she gave birth to him.

She was then sent to a Magdalene Laundry, the institutions now infamous for widespread abuse, where she spent almost 60 years before her death in 1996.

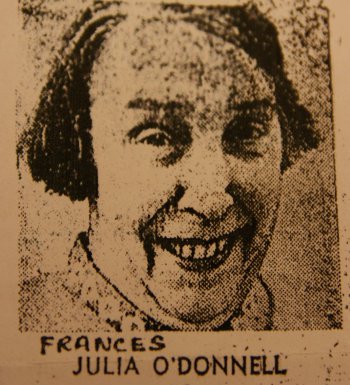

Thanks to his daughter's digging, Mr O’Donnell was then sent the only file on his mum held by nuns, a clipping of a newspaper story about when she was reunited with her first son after 33 years.

It included the only pictures Mr O’Donnell has ever seen of his mother and his brother.

“If I could have met my mum I would have asked her why I was separated from my brother,” he said.

“At least if we were both in the same place we would have known one another and would have had someone in the world.

“Now I will never know unless I get to meet my brother. I wonder if she told him who I was or if she had forgotten all about me.”

Without meeting his brother, the only physical connection Mr O’Donnell will have ever had with his family since his birth will be with his mother’s grave in Cork.

“I cried my heart out when we went to visit the grave last year,” he said.

“I am angry at the Government more than anyone else about what happened to me. They should have been taking out adverts in papers over here telling us how to find our relatives in Ireland.

“This is my life and I really feel down and out because I never got the chance to meet my family.”