I SHOULD have been looking forward to meeting Kodaline. The young Irish four-piece is, by all accounts, destined for the celestial bodies.

They have sold out shows in Dublin’s Olympia without breaking a sweat. Their hit music video All I Want has more than three million YouTube views. And the BBC has singled them out as one of the hottest prospects for 2013.

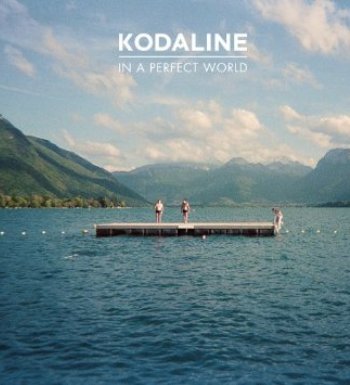

Most auspiciously of all, Kodaline has been endowed with those markers before their debut album — In a Perfect World — has even seen the light of day.

But by the time I set foot on the polished white stairs of the sweet-smelling and glass-clad west London studio where the young men were catching a glimpse of the kind of life that could be theirs, it had become impossible to shake the fear that this was going to be a painful experience.

Here’s why: find a computer, type www.kodaline.com into the internet browser, click ‘About’, read away. “For Kodaline, music isn’t just music. ‘It’s therapy,’ says singer Steve Garrigan,” proclaims the pompous prose at its opening. Then it gets worse.

These guys, pictured above in casual black-and-white, where they dare not commit the unforgivable faux pas of looking into the camera, draw their inspiration from “break-ups”.

The four men in their early twenties maintain “an air of understated mystery”. And they formed their band over “late night sing-a-longs”. Mercifully, the passage concludes: “Kodaline are now they’re [sic] hoping their music will provide therapy for others too. ‘Music should have a purpose, you know,’ says Steve, ‘Our purpose is honesty.’”

Could it be? A band grown in the image of… Nickelback? Naturally, such harshness would be deplorable if it were not about to be somewhat upended.

It was the arch-therapists who awaited me at the top of the stairs — lead singer Steve Garrigan and guitarist Mark Prendergast. Apologising for any effects that jet-lag may have on their responsiveness (they flew back from the US last night) and for the absence of drummer Vinny May and bassist Jay Boland, the pair slump onto a couch beside one another.

Over the next 45 minutes, they would prove to be at least more complex than the unflattering caricatures painted by their own words.

“I remember when we started writing songs properly, man,” says Garrigan softly, clutching his crumpled blonde curls with one hand and motioning in the direction of his bandmate with the other. “You were on the dole and when I dropped out of college I was doing nothing. I was just playing in wine bars and, sh*t, every day I would be in Mark’s house writing songs.

“We were just doing it because we had to. He was going through break-ups and so was I, so we said, ‘F**k it, let’s write some music.’”

A bad start, perhaps, except for the fact Garrigan’s words point to a more revealing portrait of Kodaline’s inception — a version of events that had been glossed over previously by lazy PR people and over-enthusiastic journalists.

The break-ups were clearly important, but their venture towards In a Perfect World immediately seemed less contrived, less aimed at honesty-with-a-capital-h, and more of an organic response to finding themselves — along with May (but before they met Boland) — with nothing to do and little to be optimistic about in their Dublin hometown of Swords.

The pair quickly nod in agreement at the words “organic process”. “Dropping out was like hitting rock bottom,” the frontman explains, hands in his hair again.

“I had been studying law and economics and it was soul-destroying, man. Jesus. Then the relationships thing happened.

“I know there is worse and you cannot really say that is rock bottom because there are a hell of a lot of worse things out there — there are people who are homeless and sh*t — but for me that was pretty f**king sh*t.

“So I sat down and wrote High Hopes (track four on In a Perfect World).” Sensing his moment, Prendergast leans forwards and interrupts: “Then he played it for his dad. And his dad said, ‘Ah sure it’s good. So are you going to college tomorrow?’”

Laughter bellows out from each man and disturbs a room full of Sony employees working in the adjoining office. The singer resumes: “I guess I had this moment when I dropped out and I did not have any plan. High Hopes is actually the oldest song on the album. I wrote it four years ago.

“That was the first song that gave me the sense that this sums up exactly how I am feeling. So I just sat there playing it over and over and over again.”

Their relative desolation would have been harder to take, perhaps, because the three had enjoyed such unprecedented success two years previously under a different name. As 21 Demands they finished second in RTE talent show You’re a Star before becoming the first independent Irish band to record a number one single with Give Me a Minute.

But as Kodaline, their route was much less immaculate. It was hindered and delayed by a series of rejections and one painful false start after they finally earned the attention of indie record label B*Unique.

“They certainly turned us down a few times,” says Garrigan. “I remember the first time B*Unique were interested. They sent us over to work with a producer, Steve Harris (of U2 and Kaiser Chiefs fame).

“We were so shy that I would not sing for him. I would not play any songs and it got to the point that he stormed out of the studio and told us to f**k off. We did not see him again for another year-and- a-half — or maybe two years — and there was just nothing happening in that time.”

When Kodaline returned to Harris’ Yorkshire studios, Garrigan was able to pluck up the courage to sing and they soon got to work on In a Perfect World.

Such is the nature of the music industry that, after three EPs, Kodaline’s debut LP is essentially in the rear view mirror before its release. That’s not to say it is not eagerly anticipated by thousands of fans, but the band has been playing the same songs for years now.

Kodaline's In a Perfect World is out now

Kodaline's In a Perfect World is out nowAnd they have already started playing new material at their gigs. That begs the question of what, exactly, second album Kodaline looks like.

The first is vocal-heavy, musically uncomplicated and generally emollient soft rock. Its key themes — which sometimes venture into the mundane — are split evenly between lamented personal loss in the likes of All I Want and Talk and the immense psychological effort needed to escape a rut, as exemplified by High Hopes and Brand New Day.

All of that fits within the picture painted by Garrigan and Prendergast of their personal situations when they wrote the songs.

But what, if music is therapy for them, could the young men possibly need to process after spending a year on tour, away from the slings and arrows that brought them to music previously?

For the first time, words come more quickly to the guitarist than to his band-mate. Prendergast says: “I think there is actually a lot more to write about because we are going to places we had never even dreamed of going to.”

It seems to stir something in the singer. “When we were touring in America for a while we were jamming and busking, writing songs about what we saw,” he says, his voice less soft now and more enthusiastic.

“We were in this place called Hot Springs in Arkansas. Al Capone used to own a bar there.

“It is really, really Southern and stereotypically… Southern. We met a guy called Chicken Hawk who was like, ‘Ahm gowne cook yoo guys a Southern breakfust’. And Deputy Dan. Woo, sh*t Dan!

“It is the kind of a town where up to the 1960s there still would have been gun fights and illegal gambling. It was crazy. And Al Capone’s bar was the centrepoint of all that.

“But we went in — it was called The Ohio Club — and it was a blues jam. So we just got up and played blues songs all night with the locals.

“The musicianship was unbelievable. At one point we were just jamming and the chef came out and was like, ‘Yeah I’ll play’. And he just sat on the piano and was like Billy Joel, man. He was putting us all to shame.”

Prendergast adds: “All the waitresses and barmen sang. The only person who did not sing was the bouncer.”

Garrigan again: “And he was probably amazing but was having a night off. At the end of the night there were 14 or 15 people on stage, including one of the best harmonica players I have ever heard.”

As they tell a series of other tales from their time in the States, including the performance they gave in Boston shortly after the bombings that rocked the city, the point seems to be that Kodaline will be less introspective and more outward-looking in future.

That, coupled with their love of Bruce Springsteen — “Soon I will be going around knocking on doors saying, ‘Have you heard about the Gospel of Bruce?’” laughs Garrigan — points more believably to the potential for Kodaline to fulfill the hype around them than the early markers do.

But the singer insists he can’t move too far from one of the main forces that drove him to a piano during those empty days in Swords. “Dude, I do not know whether you have ever been in a relationship and have been f**ked over big time, but that stays with you forever and it changes you as a person,” he says.

At this stage, it is no longer possible to avoid the subject that seemed fit to draw cringes. “We were going out for two-and-a-half years, but we had known each other for years before that. “Then one day she was like, ‘Um it is not really working out, let’s go on a break’. So she went on holiday and she came back with a boyfriend. Then, two weeks later, she moved away to the UK with him and I have not seen her since then.”

It’s no Romeo and Juliet. But within the context of Garrigan’s other struggles at the time, it is easy to see why he would have been moved to write something as stained with desperation as All I Want.

It would be dishonest to say that Garrigan and Prendergast entirely defied my low expectations. As likeable as they proved to be, they were at times as callow as their ‘About’ passage suggested.

There will be nobody greeting In a Perfect World with the time-honoured cliche that its writers must be “old heads on young shoulders”. They aren’t. That is manifested equally in person when they utter banalities like “Every song is like a page from our diary” or “There are plenty more fish in the sea” and when their first port of call for a simile is Harry Potter (“We could not find this bar, it must have been hidden down some alleyway like something out of Harry Potter.” “Yeah man, like it’s on Platform 93⁄4.”).

The two men also don’t show any discernible rock star credentials. It takes some effort to get them to admit that after gigs they occasionally venture slightly beyond “a couple of beers together” (“We are not little nuns, we do have fun. But we are not Pete Doherty either”).

And they boast that while on their three-week tour in America they “did not have a single argument about anything”. But it was probably unfair to try to squeeze Kodaline into a stereotype by expecting them to be as fascinating as Elliott Smith and as rock and roll as Liam Gallagher.

Both admit they are “still young and stupid and naive” while Garrigan is the first to notice when he has blurted out a cliché. More importantly, though, any perceived artistic shortcomings seem to be a result of the fact they feel so lucky to have gotten from where they started to where they are now.

They don’t go out partying on their nights off because they are busy playing for free at whatever open mic night, blues jam or busking spot they can find. “We have done nine free shows in one day before,” says Prendergast. “We are doing one tonight actually. We land in Dublin at half-ten and will go straight to a bar. We only do it because it is fun, not for any other reason.”

Even now, as In a Perfect World is set to be released and the band prepares for a summer of festivals that will take them from Cork to Tokyo, Garrigan and Prendergast look to the future with the kind of fear you would expect from two people who are not taking their fortune for granted.

“There is so much uncertainty,” says Garrigan thoughtfully. “This whole thing could implode tomorrow.”

Prendergast interrupts: “Our album is not out and there is competition out there.” Garrigan adds: “And even if the album does come out it might do well, it might not. There is always that uncertainty. You may as well have High Hopes — excuse the pun — because it all comes back to positive thinking.”

And the guitarist concludes: “It does not matter if you are signed, if you are going here, if you are supporting this band, people might not get behind you and you could just be forgotten about by the time the summer is over. So we are kind of fighting for our lives in a way.

“There is so much music out there. That is why we are just constantly writing and playing and doing what we do anyway. We always have that uncertainty.”

In a Perfect World is out now