THE Black and Tans and Auxiliaries have merged into one unholy entity in Irish nationalist mythology, but there were differences.

The Black and Tans were mostly former enlisted British soldiers recruited into the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) as a Special Reserve.

The Auxiliary Division was a smaller, better paid, ‘elite’ force of former British Army officers, and was also an adjunct of the RIC.

The ‘Auxies’ as they were known had garnered an even more notorious reputation than the Black and Tans for summary executions, torture of prisoners and retaliatory burnings of property.

One fifth of the Auxiliary Division was based in Cork, which was the most violent county in Ireland during the War of Independence from 1919 to 1921, with 528 fatal casualties.

The Cork Irish Republican Army (IRA) was recognised as the most effective and the most ruthless in the country.

Flying columns ranged across rural areas of the county, and in Cork city, a shadowy war of assassination and retaliation between the IRA and Crown forces raged throughout 1920.

Cork city endured much during that turbulent and bloody year.

Two Lord Mayors died: Tomás Mac Curtain, at the hands of vigilante police officers and the second, Terence MacSwiney, on hunger strike.

In November and December, the IRA killed six suspected British intelligence officers, two Auxiliaries and four civilians suspected of ‘spying’.

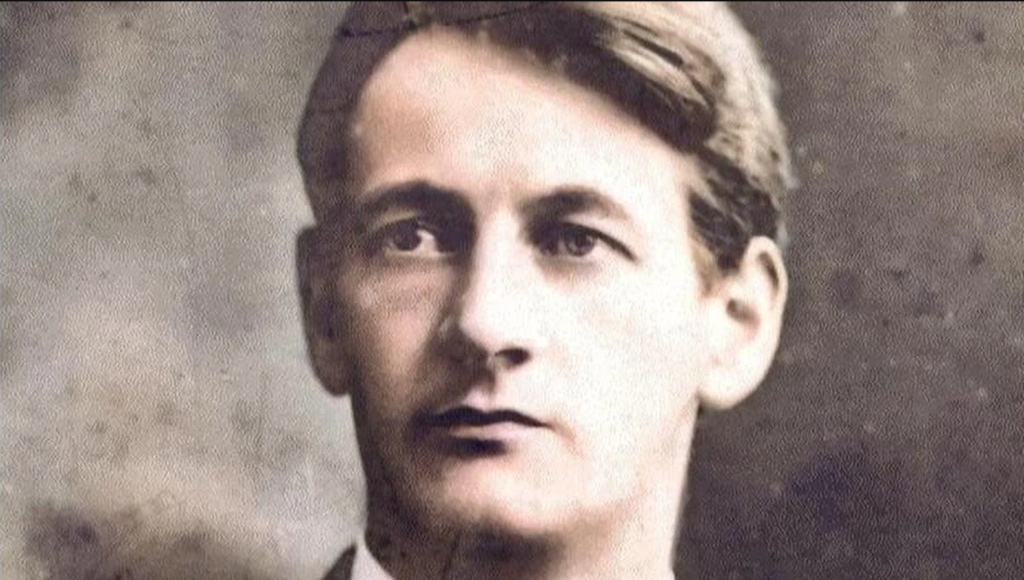

Former Mayor of Cork, Terence MacSwiney

Former Mayor of Cork, Terence MacSwineyOn November 28 a patrol of Auxiliaries was ambushed by an IRA flying column near Kilmichael, Co. Cork and 17 were killed.

Martial Law was declared in Munster on December 10 with a 10pm curfew.

Tension in Cork, especially in the city, was high and there was a palpable sense of foreboding.

On the evening of December 11, a lorryload of Auxiliaries was ambushed by the IRA at Dillons Cross near their base at Victoria Barracks.

Twelve were injured and one Auxiliary later died of his wounds.

This was what the citizens of Cork, who had first-hand knowledge of Auxiliary retribution, dreaded.

Auxiliary reinforcements who arrived on the scene raided nearby houses and set several of them alight.

Later in the evening another detachment of Auxiliaries drove to the centre of the city where they stopped a tram and set it ablaze.

In St. Patrick Street, the main shopping throughfare, they smashed the doors and windows of Grants department store and set it alight with incendiary bombs and petrol.

Cork’s two other department stores, Cashs and the Munster Arcade, were also torched as the Auxiliaries worked their way down Patrick Street.

The fires in Cashs and the Munster Arcade quickly spread and most of the shops on one side of Patrick Street and some on the Grand Parade, were completely destroyed.

Some of the Auxiliaries then made their way across the river to the City Hall, which had become a symbol of resistance since the death of the two Lord Mayors.

This was also torched, as well as the Carnegie Free Library in Anglesea Street.

Both buildings were within shouting distance of the RIC headquarters on Union Quay, but the remnants of Cork’s police force took the view that discretion was the better part of valour and declined to confront the enraged and heavily armed Auxies.

Cork Fire Brigade attempted to deal with some of the fires but were shot at and roughed up by the Auxiliaries and four were injured.

They also cut the fire hoses with bayonets and turned off the fire hydrants.

Although there were no fatalities related to the burning of the city centre, a group of Auxiliaries raided the home of two known IRA men in Dublin Hill, Cornelius and Jeremiah Delaney.

Neither had taken part in the Dillons Cross ambush but both were shot.

Jeremiah died instantly and Cornelius died of his wounds six days later.

Members of K Company were quickly redeployed away from the city to West Cork.

Four days later they were involved in the murder of an elderly priest, Canon Magner, and a young man in Dunmanway.

They were walking on a country road and had stopped to help Patrick Brady, the Resident Magistrate for Skibbereen, whose car had broken down.

He was lucky to escape with his life.

A report in the Times claimed that the Auxiliary cadet who carried out the shootings had been drinking heavily.

He was tried at a Military Court and found to be insane and committed to a criminal asylum.

The response of the Irish Secretary Sir Hamar Greenwood was nothing if not predicable.

In the House of Commons on December 13 he claimed that the conflagration in Cork had been started by Sinn Féin.

However, an enquiry by Major-General Sir Edward Strickland, Commander of the British Sixth Division in Cork, found K Company and several members of the RIC responsible.

The enquiry attempted to blame the Fire Brigade for failing to stop the spread of the fires but ignored the evidence that firemen had been shot at and prevented from doing their job. The Prime Minister David Lloyd George refused to publish the report on the basis that ‘it would be disastrous to the Government's whole policy in Ireland’ (the report has never been published but can be read in the Public Records Office in London).

Cork city, as it stands today

Cork city, as it stands todayThe government’s response was hardly surprising as the distinction between officially sanctioned reprisals and freelance vigilantism by Crown forces was always tenuous. However, the burning of Cork and the other atrocities committed by the Auxiliaries and the Black and Tans were not only morally repugnant but a public relations disaster for the British government.

Ireland, after all, was still a part of the United Kingdom and both these forces were supposedly the lynchpin of law and order acting to put down republican lawlessness.

But, by the end of 1920, it seemed the rule of law had completely broken down.

As a result, moderate nationalists who did not support Sinn Féin or the IRA were alienated; liberal opinion in Britain was outraged and practically all the British press condemned the arson.

For example, The Manchester Guardian called it ‘the crowning wickedness of the reprisals compaign’.

In addition, the Irish diaspora, especially in the United States, was galvanised, and the British claim to moral superiority in Ireland was significantly tarnished.

No one was ever charged with the most wanton act of destruction in the Irish War of Independence, although Lloyd George ordered the disbandment of K Company and the dismissal of its commanding officer Colonel Lattimer.

In 1922 the British government accepted liability to the value of £3million for the destruction of Cork city centre and the unlawful killing of the Delaney brothers.

However, Cork would have to go through another seven months of purgatory before a truce was called in July 1921 and its traumatised citizens could breathe a little more easily.

Dr Patrick Murphy is a member of the Nottingham Irish Studies Group and Chair of Nottingham Irish Centre. He is presenting a series of online lectures at the University of Liverpool to mark the centenary of Irish independence. These can be booked individually in the New Year here.