FOLLOWING a meeting between government ministers and victims’ groups in Derry last week, the secretary of state for Northern Ireland Shailesh Vara said that the controversial bill could still be open to changes.

The legislation, known as the Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill, has not so much divided opinion as united it. Unusually for Northern Ireland, both sides of the political divide are opposed to the bill, which offers a conditional amnesty to those accused of killings and other Troubles-related crimes.

The bill specifically says that it will “address the legacy of the Northern Ireland Troubles and promote reconciliation by establishing an Independent Commission for Reconciliation and Information Recovery.” The bill will also limit “criminal investigations, legal proceedings, inquests and police complaints, extending the prisoner release scheme in the Northern Ireland (Sentences) Act 1998, and providing for experiences to be recorded and preserved and for events to be studied and memorialised”.

Boris Johnson’s government introduced legislation in May in attempt to draw a line under the Northern Ireland Troubles by dealing with so-called ‘legacy issues’ — in other words more than 1,000 unsolved or unresolved killings. They range from alleged killings by British soldiers to alleged killings by paramilitaries on both sides.

Under the bill, immunity from prosecution will be offered to those who co-operate with Troubles' investigations run by a new information recovery body.

It is this “limiting of criminal investigations and legal proceedings” that victims’ groups and political parties at Stormont are particularly objecting to, arguing it will remove access to justice for victims and their families.

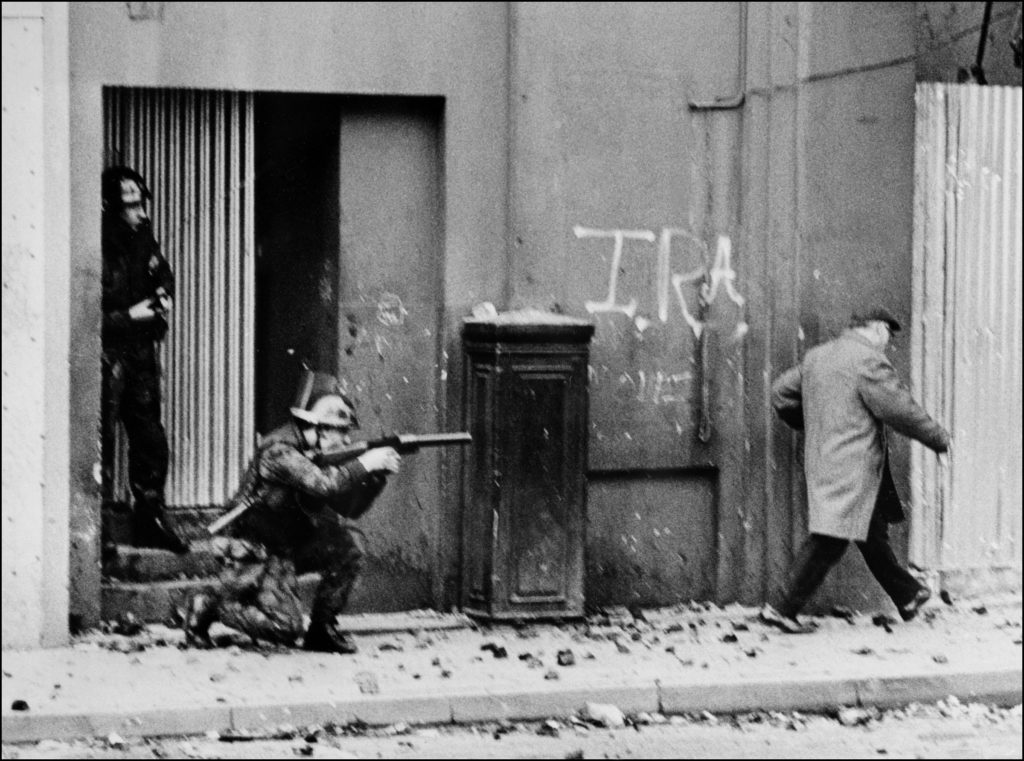

British army soldiers patrol 04 November 1971 in the Bogside quarter of the city of Londonderry during heavy clashes between the Catholic minority, loyal to the Irish Republican Army (IRA), and Protestants. Between 1970 and 1971, the IRA took up arms while Protestant loyalist militias attacked Catholics. Since the partition of Ireland in 1921, the IRA has fought for a complete withdrawal of British troops from Northern Ireland and a reunification of the island of Ireland. Around 3,500 people have died and almost 40,000 have been injured in sectarian violence involving the IRA and pro-British-rule unionist paramilitaries--the so-called loyalists. (Photo credit should read DARDE/AFP via Getty Images)

British army soldiers patrol 04 November 1971 in the Bogside quarter of the city of Londonderry during heavy clashes between the Catholic minority, loyal to the Irish Republican Army (IRA), and Protestants. Between 1970 and 1971, the IRA took up arms while Protestant loyalist militias attacked Catholics. Since the partition of Ireland in 1921, the IRA has fought for a complete withdrawal of British troops from Northern Ireland and a reunification of the island of Ireland. Around 3,500 people have died and almost 40,000 have been injured in sectarian violence involving the IRA and pro-British-rule unionist paramilitaries--the so-called loyalists. (Photo credit should read DARDE/AFP via Getty Images)The BBC reports that Minster Vara said in Derry that the bill was a ‘a way forward’ for some people, but there was no one solution that would fit all in the North.

But he added, significantly, "The bill going through Parliament is still open to negotiations, we are in listening mode, there is still room for making amendments."

Northern Ireland junior minister Lord Jonathan Caine, described as “one of the foremost experts on Northern Ireland” was involved in the lengthy talks with victims' groups and the Victims Commissioner for Northern Ireland, Ian Jeffers.

Speaking about the legislation, Mr Jeffers told BBC News NI: "We're in this stark reality that the bill is going to go through.

"I now as commissioner have to decide are there ways we could at least amend this bill to make it slightly more palatable."

Protesters who gathered in Derry during Minister Vara's visit included Billy McGreanery, whose uncle, also called Billy McGreanery was shot dead by the British army in Derry on September 15, 1971

He told the BBC his family will never stop seeking justice.

According to the Pat Finucane Centre, Billy McGreanery “was killed by a single aimed shot fired from Bligh’s lane observation post while talking to a group of friends in his own neighbourhood at the junction of Westland Street and Lonemoor Road. We believe that Billy was murdered in retaliation for the fatal shooting of soldier at that base earlier that day. Billy was branded a gunman to justify the killing even though forensics and numerous eye witness statements supported Billy was unarmed. Even the RUC and Crown Council believed that the soldier had committed a murderous act. This prosecution process was halted by the

then Attorney General Sir Basil Kelly who after secret meetings with MOD ruled that no soldier could be held accountable for any wrongdoing whilst performing his duty.”

It is cases like these that make the Legacy Bill, as far as the victims;’ families are concerned, completely untenable