Former Irish Post journalist RONAN McGREEVY speaks about his latest book, co-written with Tommy Conlon

THE kidnapping of British businessman Don Tidey in December 1983 and the shooting dead of two Irish security forces personnel brought a level of revulsion in the Republic against the Provisional IRA not seen before in the Troubles.

Private Patrick Kelly, a 36-year-old father-of-four from Moate, Co. Westmeath and Recruit Garda Gary Sheehan (23), from Carrickmacross, Co. Monaghan, were shot without warning when they came across the hideout in a Leitrim wood where the hostage had been kept for 23 days.

Mr Tidey was the chairman and managing director of Quinnsworth, then the largest supermarket chain in the Republic with 57 stores. Quinnsworth was part of the Anglo-Canadian retail giant, Associated British Foods, and was owned by the wealthy Weston family. The Provos demanded £5 million for Tidey’s release.

He was born in the East End of London in 1935 and evacuated to rural Sussex during the Second World War. He came to Ireland in 1965 as an up-and-coming supermarket executive to work for Ben Dunne Sr, the owner and founder of Dunnes Stores.

Tidey’s nationality was incidental to his kidnapping by the Provisional IRA. After all, the Provos had kidnapped Ben Dunne Jr, two years previously and previous to that Dutch man Tiede Herrema.

In the chaos which followed the shooting dead of Kelly and Sheehan on December 16, 1983, Tidey made his escape. A day after his rescue, he gave a short press conference outside his home in Dublin where he thanked those who rescued him and expressed his condolences to the families of those who had been killed.

Tidey then leaned over to give his 13-year-old Susan, who was with him when he was kidnapped, a hug and the press got their shot of a family happily reunited after a terrible ordeal.

At the same time as he was speaking, an IRA unit detonated a car bomb outside Harrods in Knightsbridge, London’s most famous department store. Knightsbridge was socially and economically the antithesis of a remote hillside wood in Co. Leitrim, but there was no locale spared by the Provisional IRA in pursuit of their aims.

Six people, including three policemen, were killed. More than ninety people in total were injured. The blast destroyed twenty-four cars and shattered windows on five floors of the department store. Eyewitnesses spoke of glass falling on their heads like hailstones. One woman lay on the ground with shards of glass protruding from her stomach as her eleven-year-old daughter screamed for help. Blood mixed with rainwater in the gutters outside Hans Crescent.

It was the third major bomb attack in London by the Provos in eighteen months. On 20 July 1982 they detonated explosive devices in Hyde Park and Regent’s Park. The Hyde Park car bomb was particularly gothic. It consisted of eleven kilograms of gelignite and fourteen kilograms of nails. The bomb was designed so that the nails would become projectiles capable of piercing flesh and causing mortal injury.

It exploded as soldiers of the Household Cavalry passed by on their way to the changing of the guard. Four soldiers from the Blues and Royals were killed and seven horses were either killed or put down. The attack produced some of the most harrowing photographs of the Troubles. The sight of the dead mounts lying in pools of blood outraged the animal-loving British public. It also embarrassed many people in Ireland, given the country’s famed love for horses.

The second attack, at 12.44pm targeted the Royal Green Jackets military band which was performing in Regent’s Park. Seven bandsmen were killed and eight civilians were injured.

These were military targets, but the Harrods bomb was an attack on civilians out doing their Christmas shopping.

It appalled the large Irish population in Britain which had frequently been targeted and smeared as a result of the activities of the IRA there over the previous decade.

“They mustn’t consider us as being Irish if they are prepared to make us victims of the type of action they have taken,” Bernadette Casey, a second-generation Irish woman living in Kilburn, told RTÉ reporter Joe Little on the day after the bombing. Parishioners leaving the Sacred Heart Church in Kilburn were angry. “I feel ashamed really. Some of my best friends are English people,” said one man. “We are disgusted, thoroughly ashamed. It’s not in the name of the Irish people,” a woman added.

Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock told Little that British people understood that ordinary Irish people living there were in “great numbers respected members of the community. The British people understand they are as different as any normal person to bombers who put themselves outside the ranks of humanity. Irish people are as disgusted and revolted and as angry with crimes of this kind as any other group in the population.”

Gerald Kaufman, then a Manchester MP and a senior member of Kinnock’s front bench, added: “I represent many Irish people in parliament. My Irish constituents are as disgusted, horrified and angry as anybody else in this country.”

There was revulsion everywhere that the Christmas of so many blameless families had been destroyed.

Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich, the Catholic Primate of All Ireland and Archbishop of Armagh, was particularly conscious of the juxtaposition between the Harrods bomb and the proximity to Christmas.

“It was nothing short of blasphemous,” he declared, “to inflict such an appalling toll of death and injury on innocent men, women and children when they were preparing to celebrate the coming of the Prince of Peace.”

Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald sent a message of sympathy to his UK counterpart, Margaret Thatcher, after the Harrods attack, which pointedly included a reference to the “tragic murder of two members of the security forces” in Ireland the day before.

In linking the Harrods atrocity with the murders of Sheehan and Kelly, Dr FitzGerald identified the Provisional IRA as a common enemy of both countries. His comments evidently had an impact on the thinking of Thatcher, who hitherto had been downright sceptical about the Republic’s attempts to combat the Provisional IRA.

The deaths of Kelly and Sheehan brought home to her that the Republic too was being targeted by the same terrorists.

FitzGerald made his point in an op-ed published in The Times newspaper during Christmas week of 1983.

“The Irish people feel this Christmas a stronger sense of shared grief and shared outrage with the British people than at any time I can recall.

“It may not be fully understood in Britain that the abhorrence of Irish people at this event is especially strong because the explosion was caused by criminals who, with no justification whatsoever, purport to create enmity between us and the British.”

The Harrods bomb amplified the sense of disgust in the Republic which followed the events of Derrada Wood. There was talk of banning Sinn Féin, then a fringe party in the South, but it was agreed that it would be counterproductive given that surveillance of known members had helped gardaí to find Don Tidey.

Instead, government ministers boycotted meetings with Sinn Féin councillors even if the issues involved were local. The killings of Kelly and Sheehan made extradition much more politically palatable. In March 1984 Dominic ‘Mad Dog’ McGlinchey, the INLA gunman who boasted of having killed at least 30 people, became the first suspect to be extradited during the Troubles.

The twin atrocities before Christmas 1983 would have long-term political implications for relations between Britain and Ireland. Thatcher was persuaded of the necessity of greater cooperation with the Republic.

After the Enniskillen bomb of 1987, the journalist Ed Moloney observed: “There can be little doubt that the Harrods/Tidey episode laid the foundations for the Anglo-Irish Agreement.

“The deaths at the hands of the IRA of Irish security force personnel in the Ballinamore woods and of English policemen and civilians in Knightsbridge dramatically brought home to both governments the lesson that they faced a common enemy.

“This added urgency and direction to the then inter-governmental conversations and in the nine months leading to Hillsborough it was a recurring theme in the negotiations.

“It only needed Sinn Féin’s electoral success in the north and the threat of success in the south to add the necessary catalyst for a common alliance and strategy to defeat the IRA.”

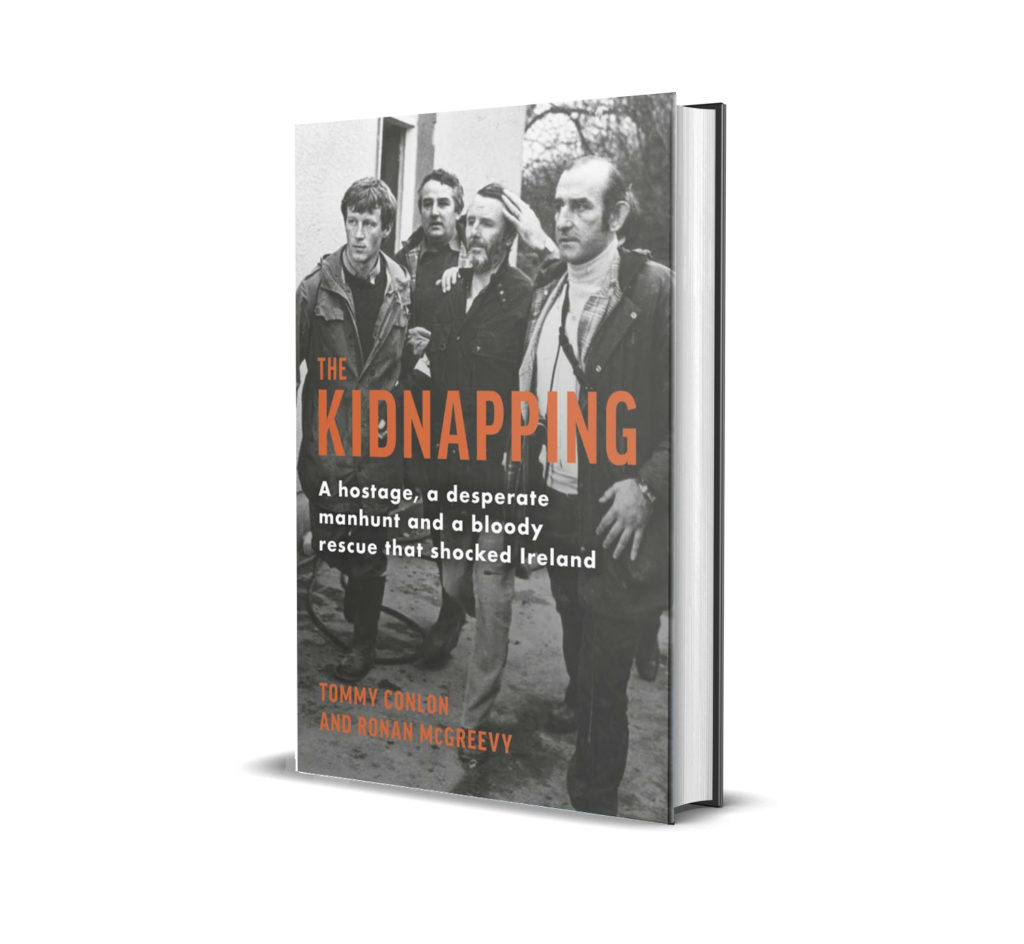

The Kidnapping: A hostage, a desperate manhunt and a bloody rescue that shocked Ireland

By Tommy Conlon and Ronan McGreevy

Published by Penguin Sandycove priced £16.99