I HAVE always loved the stained glass of Ireland’s most celebrated artist in that medium, Harry Clarke (1889–1931).

I first encountered his dazzling array of colours and illustrations at the age of ten, during a visit to Mount Melleray near Cappoquin, Co. Waterford.

There, with my family, I saw the glorious Assumption of Mary window, depicting the Madonna flanked on either side by two Cistercian monks in their white habits.

Sadly, that monastery closed earlier this year.

Since that first encounter, I’ve travelled across Ireland and Britain to see as many of Clarke’s windows as possible.

I’ve also given talks at Irish festivals, speaking about his extraordinary body of work.

Whenever I speak about Harry Clarke, I make a point of sharing the story of his tragically early death from tuberculosis in 1931, at the age of just forty-one.

His brother and extended family continued the craft under the Harry Clarke Studios, producing stained-glass windows well into the 1970s.

During his short but prolific life, Clarke personally created more than 180 stained-glass windows, not only across Ireland and Britain, but also in the United States and Australia.

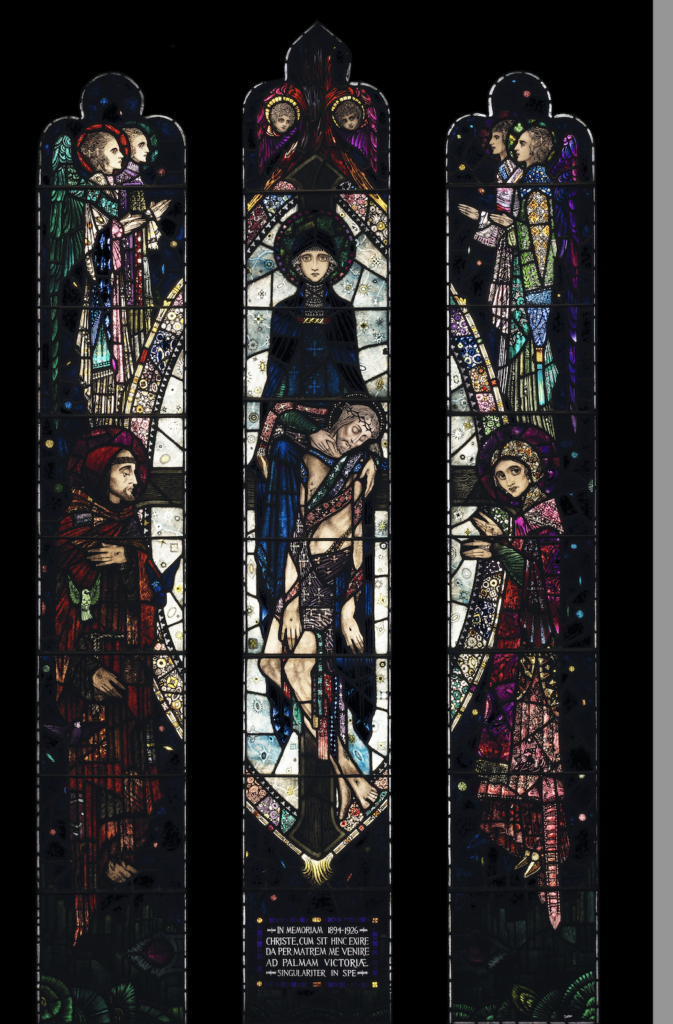

The Mother of Sorrows, 1926 by Harry Clarke (Pic: National Gallery of Ireland)

The Mother of Sorrows, 1926 by Harry Clarke (Pic: National Gallery of Ireland)In 1922, Sister Wilfrid—Sister Superior and Principal of Dowanhill Training College in Glasgow—commissioned The Mother of Sorrows for the convent church.

The college, later known as Notre Dame College of Education, was founded in 1895 to train Catholic women as teachers.

Originally intended as a memorial to men killed in the First World War and based on the Pietà—Christ in the arms of Mary after being taken down from the cross—the window took on new meaning after Sister Wilfrid’s sudden death.

It was installed in Glasgow on 24 January 1927 and became her memorial.

In 1979, the window was moved to the sisters’ college in Bearsden, Glasgow.

It was later purchased by the Irish State at Christie’s Auction Rooms, King Street, London, in 2002.

The window

The first light depicts two angels in prayer.

Below them, Saint Francis of Assisi is shown in a brown habit and bare feet.

In the second light, the top panel features two angels with purple and magenta wings and golden halos.

In the main panels, Mary is depicted in royal blue robes, headdress, and cloak, holding her dead son in her arms.

The third light’s top panel also depicts two angels.

Below them, Saint Catherine of Genoa—a fifteenth-century devotee of Jesus—is shown in magnificent robes of magenta, purple, ruby, and gold, with emerald sleeves.

I visited it recently and hadn’t realised it had its own dedicated room.

What a joy it was to step into a darkened space and, with the use of backlighting, see one of the finest Irish stained-glass windows ever designed and made—by none other than Ireland’s greatest stained-glass artist, Harry Clarke, assisted by colleagues from his studio.

I was keenly aware that, during the creation of this masterpiece, Clarke was in declining health, suffering from chronic respiratory problems. He died just four years later, returning from a sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland.

Other stained-glass works and illustrations by Clarke are currently on display at the spacious and newly refurbished National Gallery of Ireland.

A television documentary I contributed to, filmed at St. Oswald & St. Edmund Arrowsmith RC Church in Ashton-in-Makerfield, near Wigan, is now available online - just search Harry Clarke Irish in UK TV to find it.