MANY Irish music fans – echoing the sentiments of one of his iconic songs, Still Got the Blues – will feel a tinge of melancholy as Gary Moore’s 15th anniversary approaches next February.

The Belfast-born genius was rightly considered a legend, with esteemed publications such as Total Guitar, Classic Rock, and Louder having all hailed him as one of the greatest lead guitarists of all time.

Fortunately, his landmark 2026 anniversary now looks set to be honoured properly, with plans for a statue commemorating Thin Lizzy legend in his hometown.

Belfast City Council recently approved permission for a bronze of Moore designed by the Scottish sculptor David Annand, best known for his statue of living legend Billy Connolly in Glasgow.

"Gary was a wonderful guitar player, and I hope the joy he brought to so many with his talent will be revisited when his statue takes pride of place in his wonderful city,” the artist stated.

Gary Moore in action

Gary Moore in actionThe crowdfunding page to raise £70,000 for the bronze statue has just been set up, with the backing of the late star’s family, who suddenly passed away in Spain on February 6, 2011.

“It was overwhelming to see the first images of Gary’s statue,” said his sister Patricia about the now-completed clay model of the planned statue.

“It now feels like a reality. We always wanted this to be a statue that Gary’s fans had ownership of. We wanted to allow every fan to say, ‘I helped put this statue here’.

"It feels so close but there’s still a way to go. We are all looking forward to a day when people will visit Belfast to pay their respects to Gary and the statue.”

Moore’s career resulted in him “selling over five million albums”, according to the Irish music bible Hot Press magazine.

Born in 1952, Gary was still only a young teenager when he escaped the start of the Troubles and moved to Dublin in 1968. He soon joined one of the biggest Irish bands of that era, Skid Row, famously fronted by Brush Shields.

Moore, who was left-handed but taught himself to play the guitar with his right hand, decided to go solo in 1971.

“Skid Row was a laugh but I don’t have really fond memories of it, because at the time I was very mixed up about what I was doing,” Moore said, adding that he “hated” being treated as the band’s “little-boy” genius.

“It was too much for me to handle at the time, and the guys in the band were a lot older than me. Nobody ever said ‘well, you’re playing really good’ – they’d just leave me to it and let me work my arse off.

“Consequently, I just became faster and faster trying to probably impress them, more than anything and ended up being a lot faster than I intended to be. It was stupid really.”

In 1974, he was asked by his old Skid Row bandmate Phil Lynott to step into the shoes of another Belfast-raised musician, Eric Bell, who had just left Thin Lizzy.

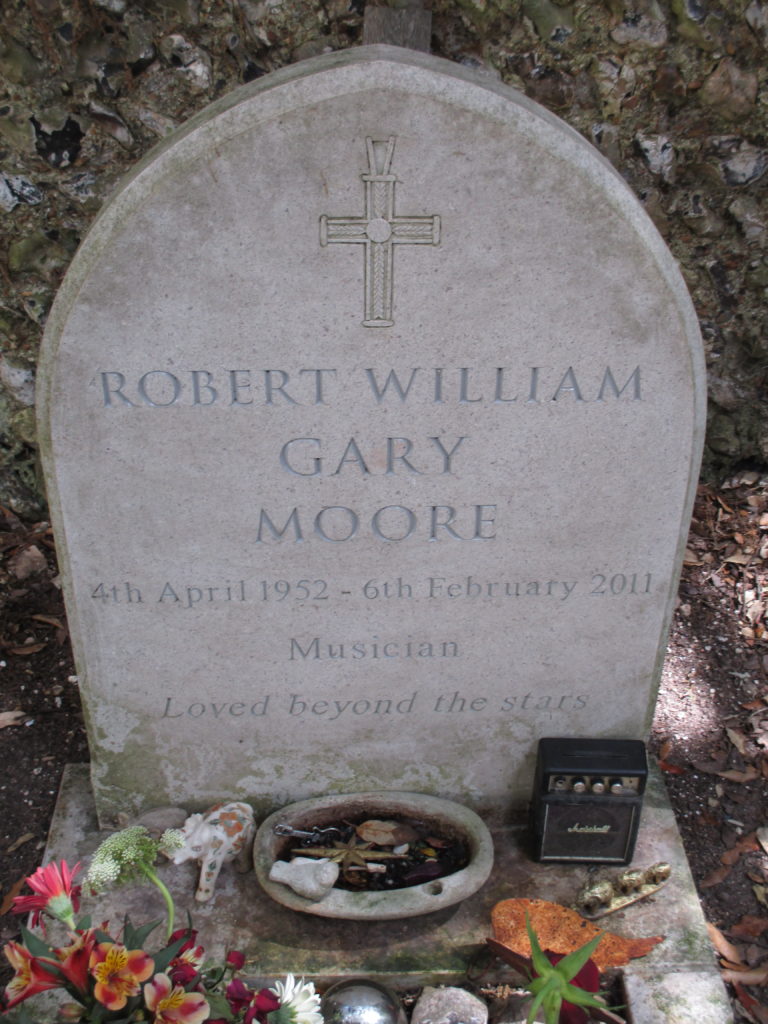

Gary Moore's grave in East Sussex

Gary Moore's grave in East Sussex“It was good for me, and they were easy for me to work with. I stayed for six months and then got very frustrated with the music. It wasn’t interesting enough to play – so I got out,” he recalled.

Moore next started an experimental band called Colosseum 11, travelling around in a minivan on tour for few years with little commercial success.

Back with the Lizzys

In 1977, he was asked to rejoin Thin Lizzy on their US tour supporting Queen when band member Brian Roberston cut his hand.

After the tour, he went back to his previous band for a couple of years before rejoining Thin Lizzy at the end of the decade to record their epic album Black Rose, which was a certified gold hit in the UK.

Once again, the reunion was short-lived – this time because Moore was exasperated by the band’s heavy drug partying and its negative effects on their live performances.

In the 1994 book Philip Lynott: The Rocker, Moore told the author Mark Putterford that he had no regrets about leaving the band.

“But,” he added, “maybe it was wrong the way I did it. I could've done it differently, I suppose. But I just had to leave.”

By the age of 30, Moore – who ended up with facial scars after being involved in a bar fight in the 1970s – insisted that his own wild days were long behind him.

“I don’t get into a lot of fights [now]. That’s going back a bit. I mean that’s when I was with Lizzy [the first time] and I wouldn’t remember half of what happened!” he told Hot Press at the time.

“It was like that – just a blur and so stupid. Not the later Lizzy but the first time round I’d do a bottle of wine before going on-stage, another while I was up there, and half a bottle of whiskey when I came off, so I wasn’t really sure of what I was doin’ half the time.

“I think, though, that I got it all out of my system in the space of two years – drugs and everything. I haven’t taken drugs for a long time now.”

Going solo

After leaving Thin Lizzy, this time for good, Moore focused on his solo career and also recorded two albums with Greg Lake of Emerson, Lake and Palmer fame in the early 1980s.

Next up, Moore enjoyed one of his biggest hit singles with Out in the Fields with his old mucker Phil Lynott, which appeared on his 1985 solo album Run to Cover. The Moore-penned tune reached number 5 in the UK Single Charts and a number 3 hit back in Ireland.

There were plenty of other collaborations along the way, including one most memorably with George Harrison, Albert King and Albert Collins on his eighth solo album, Still Got The Blues, in 1990.

The title track was Moore’s only solo song to ever chart on the Billboard Hot 100 in the US.

Moore – who also played with the likes of B.B. King, The Beach Boys and The Traveling Wilburys – was working on a Celtic rock album when tragedy struck on February 6, 2011, and he died of a heart attack in his sleep while on holiday in Andalusia, Spain. He was only 58.

At his funeral in Brighton – where he had lived for the final 15 years of his short life – one of his sons and his uncle performed Danny Boy, and the service concluded with Lois Armstrong’s What A Wonderful World. According to a report in the Belfast Telegraph, “some mourners in the church wept openly” when they heard the Irish ballad.

Speaking at the music legend’s funeral, Fr. Martin Morgan recalled how Moore had performed in a local pub to help raise funds for the victims of the Haiti earthquake.

Moore was, the priest said, “the kind of musician who would play anywhere if someone lent him an amp”.

“They asked lots of people to play but Gary was the only one who turned up. Not only did he perform, his amp broke down, but Gary kept playing and managed to finish his set,” Fr. Morgan recalled.

“He was someone who took the talent he was given and used it to touch the soul of others. I believe, for this generosity, Gary is in Heaven.”

No doubt Gary Moore will be smiling down from heaven at the news of a well-deserved statue being planned in his honour.

Donations towards the statue can be made at: www.idonate.ie/crowdfunder/GaryMooreStatue