GUINNESS heir Garech Domnagh de Brún, usually styled Garech Browne, was renowned as a party-giver, bon viveur, and traditional music lover.

He was one of Ireland’s most colourful, influential and far-seeing figures in the fields of music, art, poetry and literature.

His life’s work, Claddagh Records, became one of the most highly regarded traditional music labels anywhere.

Browne co-founded the label with his friend Ivor Browne (a medical doctor and no relation), in a bid to preserve Ireland’s musical heritage being swamped by the emerging pop and rock culture from the Britain — as he saw it.

He lamented Ireland’s showband scene where unimaginative, albeit skilled, musicians aped the music coming in from (largely) England and America.

He labelled this showband scene “a pretty frightful noise”.

Garech Browne evidently didn’t know what was likely to be the new rock & roll (to use a 21st century phrase); he knew it wasn’t showband music, and indeed was fearful it might, indeed be rock & roll.

So he set about saving Irish music from the ravages of bad pop music, country & western and country & Irish.

Garech and his label co-founder were both students of the uilleann piper and pipe maker Leo Rowsome — and both shared the same vision or preserving the precious heritage that was Irish music.

In the early days of the label New York born poet and writer John Montague was involved in the company, as well as Dún Laoghaire-based record shop owner Liam MacAlasdair.

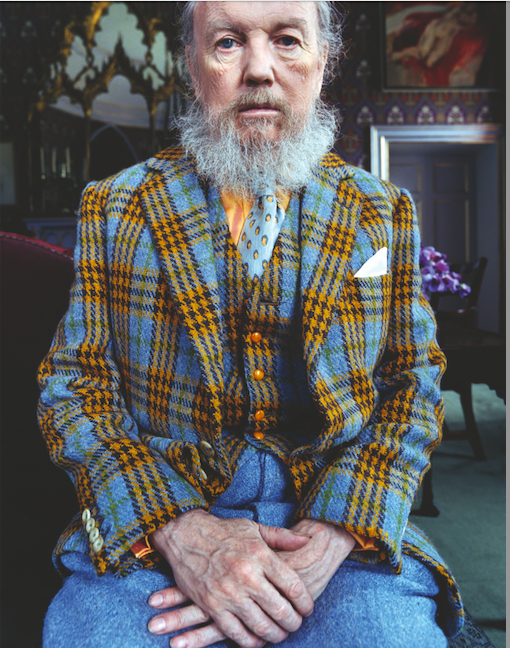

Garech Browne (Pic: Simon Watson)

Garech Browne (Pic: Simon Watson)The Guinness connection

Garech Browne, who spent his early years in Crossboyne, Co. Mayo, came from an aristocratic family that had its share of triumphs and tragedy. His father, Dominick Lord Oranmore and Browne lived to be 100.

He sat for a record 72 years in the British’s House of Lords (as an Irish peer) without ever addressing his fellow lords.

“He earned the unspoken admiration of many by never speaking in the chamber,” according to The Daily Telegraph.

Garech Browne’s brother Tara, famous as part inspiration for the Beatles song A Day in the Life, was killed in a car crash in London aged 21.

Garech, who was the great great great grandson of Arthur Guinness, lived in the family estate in Luggala in the Wicklow Mountains.

And although he was determined to ‘save’ Irish vernacular music from inroads by American-British pop culture, he was always happy to see doyens and divas of that scene at his parties in Wicklow.

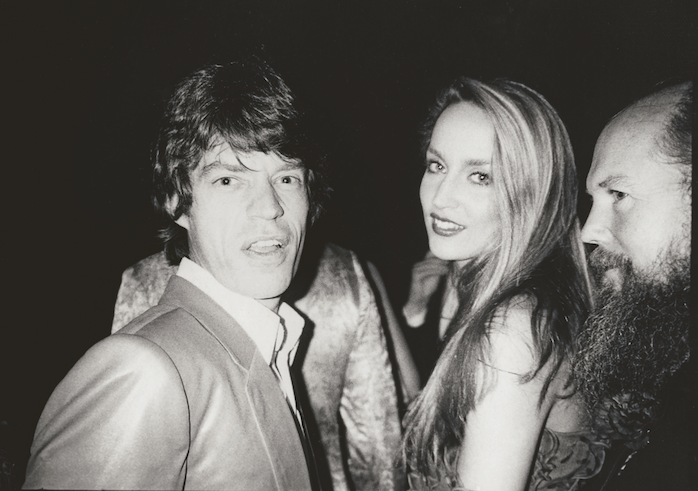

A-listers such as Mick Jagger, Marianne Faithfull, Paul McCartney, Anita Pallenberg, John Boorman, Michael Jackson, John Hurt and many more enjoyed his hospitality.

Mick Jagger, Jerry Hall and Garech Browne in 1980

Mick Jagger, Jerry Hall and Garech Browne in 1980Luggala was also a popular haunt of of the Irish cultural world, the literati , the glitterati and the bohemian — from Seamus Heaney to Edna O’Brien and from Brendan Behan to Bono.

Dublin painter Francis Bacon was an old friend, as was Lucian Freud. A portrait of the teenage Browne in 1956, Head of a Boy, sold for £5.8m at Sotheby’s in 2019.

Sean Connery, another visitor, was so taken by the musicianship of Tommy Potts that he wrote a poem about it.

“Everyone was welcome at Luggala, except people who were boring,” Browne would later reminisce.

All enjoyed the legendary parties in Wicklow — at one, Browne had The Lovin’ Spoonful flown in from California to provide music for yet another full-on, wild bacchanalian knees-up.

Yet, throughout all the partying on down, the spectre of Ireland losing its precious legacy of traditional music haunted him.

Garech Browne with singer and banjo player Margaret Barry

Garech Browne with singer and banjo player Margaret BarryThe record company

Although Browne enjoyed what might be termed a free-wheeling lifestyle, it was his efforts with Claddagh Records that makes him a such a significant figure in Irish music and Irish culture.

Claddagh Records is credited with sustaining traditional Celtic music at a time when it was in danger of dying out altogether, or at the very least becoming a very marginalized pursuit much like Morris dancing.

He assisted Paddy Moloney, his friend, in transforming Seán Ó Riada’s Ceoltóirí Chualann into The Chieftains, a hugely significant step in the evolution and preservation of Irish music.

At the end of this month, on September 29, Real to Reel: Garech Browne & Claddagh Records will be published.

This hardcover book, 12” vinyl album, and poster chronicles the stories of both the record label and the extraordinary life of Garech Browne.

It focuses not primarily on the parties and the sometime decadent lifestyle, but on what drove him to set about evolving, promoting — and some might say saving — Irish traditional music.

He had a very clear idea that Ireland’s music was an irreplaceable legacy.

Not unique, because, as he would have been the first to point out, all countries have a music tradition. No society has ever been found that has no music.

But Ireland’s musical inheritance had arrived in the 20th century with elements of a very old culture still just visible.

It had also absorbed influences across the centuries, ranging from the Norman invasion, to London’s pubs.

It was a confluence that included rural Ireland, occupied Ulster, America, Britain, religion, the Great Famine, rebellion, oppression and community.

Garech Browne knew all this, and was also well-acquainted with the traditional music that survived in rural outposts in Ireland.

During his early upbringing in Co. Mayo, his love for Irish music had begun to take root. He says: “I can remember dancing to Irish music at around the age of three.

"It is one of my earliest and most vivid memories. There was a strong tradition of Irish music in Mayo.

'Traditional music was played in homes and in neighbours’ houses on every kind of occasion, and on no occasion at all.

'There was a man who worked for my father, doing all sorts of jobs. He loved Irish music, and I would hear him whistling these tunes – and I thought they were magical. I would walk around after him. He was like my own pied piper.”

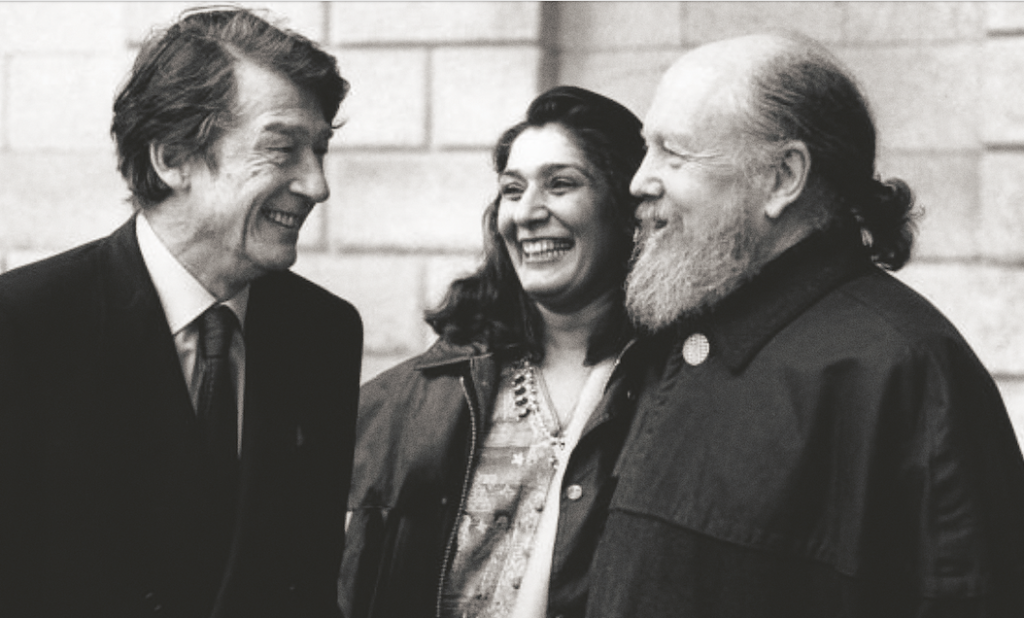

John Hurt with Garech Browne, and Garech's wife HH Princess Harshad Purna Devi Jadeja of Morvi in Bombay (now Mumbai) 1993

John Hurt with Garech Browne, and Garech's wife HH Princess Harshad Purna Devi Jadeja of Morvi in Bombay (now Mumbai) 1993When it looked possible that this precious musical heritage could be lost, Browne determined to try to help save it, and bring it to a wider public.

In rural Ireland, he knew how to track down unheralded musicians and singers — mostly totally unknown outside their immediate locality — and recorded them on an old reel-to-reel Grundig tape recorder.

His roster of artists included the singers Sarah and Rita Keane and Dolly McMahon; the fiddle players Denis Murphy and Julia Clifford; and London-based flute player Paddy Taylor — the music of these talented musicians would have been lost to posterity but for the efforts of Browne and his team.

Claddagh Records was set up in 1959 — Garech was only 19. Leo Rowsome’s Rí na bPíobairí (King of Pipers) was the first album released, and it quickly sold out — proving to Browne that a market certainly did exist fir traditional music. Browne then made a hugely significant move — some might describe it as seminal.

He persuaded Paddy Moloney to record an album with an ensemble of musicians, many of whom had played with Paddy in Seán Ó Riada’s Ceoltóirí Chualann.

Moloney took the name from Montague’s story, Death of a Chieftain and the album was simply called The Chieftains. It was one of the first folk albums to be recorded in stereophonic sound.

The band’s success was given a huge boost when their version of Mná na hÉireann (Women of Ireland) became an integral part of Leonard Rosenman’s Oscar-winning score for the 1975 film Barry Lyndon.

This was followed up by some of the most significant names in Irish music: Sean Ó Riada, Liam O’Flynn Seamus Ennis and Matt Molloy.

Not everyone was convinced: Erskine Childers, later President of Ireland, asked Browne why he wanted to issue recordings of “squealing pipes and old women wailing songs” when they were trying to promote a more modern Ireland to the world.

Poetry also represented a significant output of the label: Patrick Kavanagh, Samuel Beckett, Austin Clarke, John Montague and Seamus Heaney, as well as Scottish poets Hugh MacDiarmid, Sorley MacLean and George MacKay Browne were all recorded on Claddagh.

Garech Browne died in 2018 at the age of 78.

Patrick Kavangh and Garech in The Bailey pub, Dublin, Bloomsday, 1967

Patrick Kavangh and Garech in The Bailey pub, Dublin, Bloomsday, 1967The book

Contributions in the book include input from President Michael D. Higgins, Bono, Garech’s housekeeper Margaret Traynor and his librarian Mary Hayes.

The 228 page hardcover volume relating Browne’s story is accompanied by Masters of Their Craft, The Claddagh Collection LP presenting 17 re-mastered tracks from Claddagh’s immensely rich back catalogue, including a never-released-before poem from Pulitzer Prize For Poetry and T.S Eliot Prize-winning poet Paul Muldoon.

Performers features on the album include The Chieftains (of course) Seamus Ennis, Dolores Keane and many others. The poets featured include Seamus Heaney, John Montague and Paul Muldoon.

The publishers say: “Real to reel is an extraordinary tale that weaves stories of rugged Connemara Sean-nós singers such as Vail O Flaherty and icons such as Brain Jones into one captivating narrative.”

It would be hard to quibble with that.