RORY Delap indulged himself over Christmas — feasting on a plateful of his mother’s cooking instead of worrying about a seasonal diet of Boxing Day fixtures and relegation dogfights.

Home with his family for the first time in 20 years, three generations of Delap boys ran their eye over the Premier League drama, knowing the tension — for once — didn’t have a personal impact.

A week earlier, he’d called time on his career, two decades after he first walked into Carlisle United’s training ground on a £90-a-week YTS programme, innocent of the trials and tests which lay ahead.

“The world was a different place then,” he says. “Well, the football world was anyway.”

What happened on day one of his professional career could have broken him. Stripped naked and taken to the first-team showers, he was covered from head to toe in boot polish by the club’s older pros, a traditional initiation ceremony of the club’s.

The next day it happened again. Only this time, deep heat was rubbed rigorously around his unmentionables. Scarred? Not a bit.

When it happened a third time, he put up a bit of a fight and took a few punches to his kidneys for his trouble. Football clubs, in the early 1990s, were not a place for the faint of heart.

“I never saw it go over the line,” said Delap last week. “Close to the line, yes. Whether I set my standards high or low, I don’t know but I honestly think it prepared me for the abuse I would later get from fans, other players, from managers.

“There was a big drinking culture around then and not just at Carlisle. It existed up in the Premier League as well. Certain things happened in and around football teams which had to be tightened up.

“And what they did to me and other YTS guys was probably part of it. Looking back, I find it a laugh. What they did had a purpose. You were a 15-year-old, just out of school and landed into a man’s world, with 35-year-olds who had seen it all.

Whether they decided they would do what they did to test your mental strength, I don’t know. Maybe it happened to them when they were apprentices and they just thought this is the way of the world.

“In my age group, we took everything in good spirit. If you protested too much, put up a fight, you got a kicking and thrown in an ice bath. Those were the rules.”

Today’s rules could hardly be more different. Academies have replaced YTS programmes. The apprentices of 2014 arrive in top of the range motors, walk through club car parks like John Wayne and flash their cash. The threat of a gang-like assault is non-existent.

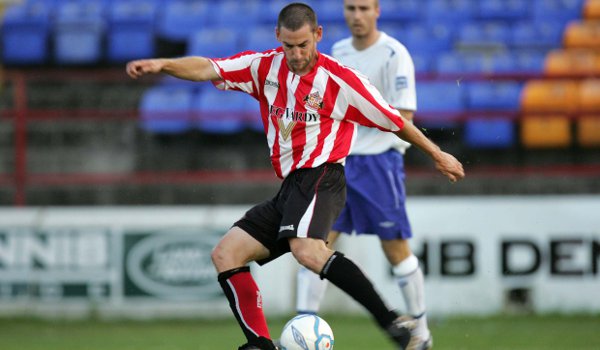

Delap had a lengthy career due to his consistency of performance

Delap had a lengthy career due to his consistency of performance“Young players are spoiled now, no question. But you can’t go back to the old ways because if one club is ploughing money into their underage set-up then others know they have to follow if they are going to compete.

“So there is no going back. But these days the apprenticeships don’t do jobs which I think is a mistake because when I was on the YTS, I was hungry to get away from there, to be sat in the first team dressing room and free of the menial tasks.

"That was character building, a motivating factor. What happened to me as a kid definitely made me as a player.”

As a player he’d go on to achieve plenty — playing over 500 first-class games, getting to two FA Cup finals, winning 11 international caps, appearing in 14 Premier League seasons and earning a hell of a lot more than the £90-a-week he started on.

Yet he knows what he’ll be remembered for.

“At Carlisle, my long throw was a weapon but other clubs never wanted to utilise it. Derby had quick forwards so the ploy then was to bang over the defenders heads and let Dean Sturridge, Deon Burton or Paulo Wanchope run onto it.

"Southampton really only used it with five minutes to go in a game if they needed a goal. Gordon Strachan would say to the centre-backs, ‘up you go’ and I’d fling it in.

“Stoke was different because we’d a huge team. When it worked for us, people slagged us for saying that all we practised was long throws and set-pieces but the truth is we trained Monday to Friday and then on a Friday, for half an hour, we’d work on set-plays.

"I’d say we’d spend five minutes a week doing throw-ins. What people forget is the bravery of the guys getting on the end of those throws. There were a lot of bust noses and black eyes in our dressing room after matches. I got the profile but they took the pain.”

Being known as the long-throw specialist is not painful to Delap, though. “Look, I was never too bothered by the label. People close to me said I would only be remembered for my throws but I’d rather be remembered for something than nothing.

“I’m not stupid enough to think I am a Ronaldo type. I was a ball-winning player who gave the ball to guys who could do decent things with it. I was half decent at that job and was rarely dropped by a manager.”

Yet there are regrets, especially around Ireland.

Part of a new wave of 20-somethings brought through by Mick McCarthy at the tail end of the ’90s, he broke into the side for the Euro 2000 playoffs against Turkey and was told that if he went on the following summer’s tour to America, it would represent a land of opportunity.

But by the time the baggage was being loaded onto the plane at Dublin Airport, Delap was a physical wreck. A season-long niggling injury to his Achilles required an injection, which subsequently became infected.

He regrets getting an injection that hindered his international career

He regrets getting an injection that hindered his international careerFor two days he couldn’t walk. And yet he hooked up with the squad and told McCarthy he wanted to travel even though he knew he couldn’t play. After much deliberation, he stayed at home.

“In hindsight, the decisions I made around then were a mistake,” he says. “That tour saw Killer [Kevin Kilbane], Dunnie [Richard Dunne] and Duffer [Damien Duff] cement their place. They’ve about 300 caps between them now but were on a similar number to me then.

"I should have just ignored the advice to get an injection and gone and played. It could have been different. Mick was great and I’ve a lot of time for the man. It was a turning point, though.

"I made every squad bar one for the next World Cup campaign and didn’t play once, only making the bench once, for the away game in Andorra. Then, when the squad was named for Japan and Korea, Mick phoned and told me I hadn’t made the cut. That was fair enough too.

"I’ve no qualms with him — I’m more annoyed with myself for getting that injection.”

As the decade wore on and he’d enjoy fine form with Southampton and especially Stoke, talk of fresh call-ups would resurface but then go away. “After a while I stopped looking at the squads. There was just no point.”

The ghost of Christmas past doesn’t haunt him, though, because as he reflected on the ups and downs of his professional career last week, it was with the knowledge that it ended up a lot better — and a lot later — than he, at one stage, thought.

Seven years ago, he was playing for Stoke against Sunderland when a mistimed tackle with Robbie Elliott saw the ball go one direction and his leg in another. “I lay there on the ground, looked down and saw my leg, essentially, was hanging off. There and then, I thought, ‘I’m finished. There’s no way I’ll play again’.

"But the next day the surgeon came in and said, ‘you’ll be okay in seven months’. And sure enough, I was. I got my second chance and some of my best years were my later ones.”

By mid-December, though, time had finally caught up with him. A persistent hamstring injury had prevented him reaching full fitness, confining him to just six appearances for League Two side Burton Albion.

“The way I play I need to be at full tilt. And I just wasn’t getting any better so rather than take the piss out of the club and pick up a wage for the sake of it, I made the right call. In the end it was a relief.”

And with his parents — John from Letterkenny and Maura from Kells — he had a special Christmas, marvelling at John’s capacity to persuade his boys — aged 10, six and four — to declare their allegiance to Ireland.

“They’ll listen to him quicker than they will me,” laughed Delap. “But you hope the importance of being Irish resonates with them. It meant everything to me growing up. We’ve gone back to the same places I went to when I was a child in Donegal and Meath. They loved it.

"Their granddad has drilled it into them that if they’re any good at anything, it’s Ireland they have to represent. When he said it, they took it all in. So that’s one issue done and dusted then.”

Just like his career. Part two of his life begins now.