MARY Hazard is one of the Irish Angels, one of the thousands of women who came to Britain in the 1950s, 60s and 70s to train and work as nurses in the NHS.

Her recently-published memoir Sixty Years a Nurse tells of what her life was like as one of the NHS’s longest-serving nurses. Here's 10 things about her remarkable life...

1. The Ireland Mary Hazard left in 1952 was one that was controlled by the Catholic Church

“My mother wanted me to train in the Mater Hospital in Ireland,” says Mary.

“She didn’t want me to go to England, which she called ‘an evil black Protestant godforsaken country’.

"But I wanted to get away from the nuns.

"All the hospitals in Ireland were run by nuns and I’d been with nuns since starting school at four. I’d had enough.”

Her mother was so resistant that she fought Mary right up to the moment she boarded the plane.

Right before she departed, she shoved a rosary, a prayer book and £20 into Mary’s hands, telling her she would need the money as she’d be home within a month.

“She’d have locked me up there and then if she could,” laughs Mary.

2. Most Irish people still felt a strong sense of animosity towards the English at that time

“Father fought for Ireland in his youth and shot a policeman,” says Mary.

“When he died, he was buried with full military honours and an IRA flag on his coffin.

My son only discovered that when he read the book – he was shocked!”

These Irish nurses took the top three places in the British Nurse of the Year Awards in 1964. Left to right Maureen Grennan, Patricia Simonds-Gooding and Dympna McGarry. Picture: William Vanderson Fox (Archive Getty Images)

These Irish nurses took the top three places in the British Nurse of the Year Awards in 1964. Left to right Maureen Grennan, Patricia Simonds-Gooding and Dympna McGarry. Picture: William Vanderson Fox (Archive Getty Images)3. Mary wasn’t the only one to choose to train as a nurse in England

It was common for Irish nurses to do so at the time.

By the early 1970s, there were more Irish-born nurses in Britain than there were in Ireland, with the Irish making up 12 per cent of the entire British nursing staff.

“You had to pay for your nurse’s education in Ireland and people couldn’t afford it,” says Mary.

“Training was free in the UK. They’d train you as long as you’d work for them for at least one year afterwards.”

A girl Mary knew from her hometown of Clonmel had previously trained in England and given her the contacts she needed to train in Putney.

“I wrote a letter and was accepted on probation,” she says.

“When I look back, it was a big step to come to England by myself but at the time, I didn’t think about it at all.”

4. Mary trained in Putney Hospital, where trainee nurses lived on site in small, cell-like rooms

They were woken at 6.30 every morning and subjected to daily inspections.

They earned £10 a month.

“We’d buy Woodbines from Bert, the porter, at four old pennies for a pack of eight,” says Mary.

“Bert would get us bottles of Merrydown cider too, which we’d drink illicitly after lights out.

"We could easily spend a third of our wages without leaving the building.”

5. Training brought its challenges, especially for an innocent, Catholic girl

Mary saw women with failed abortions.

“They’d be in a terrible state, with metal, back-street abortion implements still stuck in them,” she says.

There was venereal disease too. “It was widespread after the war,” she says.

“I remember a man with syphilis whose toes came off one day while I was changing his dressings.”

6. Mary had a particular fear of TB

It was known as the White Plague in Ireland where it had killed so many people.

It had affected her own family too, with three of her sisters sent to a sanatorium to recover.

One suffered terribly.

“Úna spent six years in a sanatorium and her entire right lung was removed as well as all her ribs down one side,” says Mary.

7. London was beginning to change at the time

Café culture had recently arrived and the trainee nurses would drink coffee and eat ice cream in Putney’s cafés and then go window shopping along the high street.

Fashion was important at the time too.

On a night out, Mary would wear a tight-waisted full skirt with a big net underskirt, an off-the-shoulder dirndl blouse, a short cardigan or bolero, stilettos and red lipstick.

She’d also have her hair in rollers.

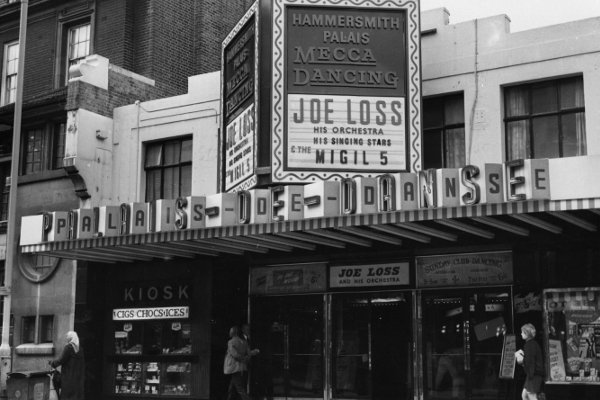

8. The nurses would often go dancing at the Hammersmith Palais

But there were rules for girls in those days.

“You couldn’t approach the bar by yourself,” says Mary.

“You had to wait for a man to offer you a drink and if he did, I’d always have a Dubonnet and lemon or a gin and orange.”

9. The men of the time tended to belong to one of several distinct gangs

Beatniks wore sloppy joe jumpers, long hair, beards and horn-rimmed glasses.

Teddy boys had sharp suits and Brylcreme-slicked quiffs.

And then there were ex-soldiers, American GIs and local police and firemen.

The trainees never told men they were nurses.

“Nurses were thought to be free and easy and we didn’t want them to think that,” says Mary.

10. Mary left Ireland in 1952 and spent the next 62 years working in the NHS

She only retired last year, aged 79.

Now that she’s retired, Mary looks back on her time as a nurse with fondness.

“I had the happiest of lives working as a proud Irish nurse for 62 years in the NHS,” she says. “I miss it terribly.”

And despite her mother’s horror of England, Mary now sees it as her home.

“I haven’t been back to Ireland since my brother and sisters died but England is my home now,” she says.

“I’ve had a good life here and if I had to live it over, I’d do it all again.”