Nemesha Balasundaram meets Scotland-based Clare man Joe Quinlivan, author of a soon to be released book about the Irish construction industry in Britain

SIXTY years have passed since Joe Quinlivan waved goodbye to his mother as he boarded a bus from his native Co. Clare in search of a better life in London.

It’s a heart-wrenching moment that he experienced as a 17-year-old, and one that he vividly remembers to this day.

Stepping into a foreign land of bright city lights and unfamiliar faces, it’s the camaraderie with Irish men like him on the construction sites that gave him a home away from home.

Joe’s story of his trials and tribulations in leaving behind his family at a time of desperation in Ireland is not, however, all that uncommon.

In his new book True to the End: A Diary of an Irish Construction Worker, due to be self-published this summer, he documents not only his personal journey but also that of “the forgotten Irish” — the hundreds and thousands of Irish men and women who were forced to immigrate to Britain in the 1950s.

The 79-year-old, now based in Falkirk, Scotland, embarked on a new life in the English capital six decades ago with just £5 in his pocket.

He left behind not only his mother, but also a brother and sister, who were just 15 and 13 at the time.

Recalling the emotional journey, which led him out of Ireland, he said: “I’d never been away from home before. I’d never been on a train, it was all new to me.

“During the train journey from Limerick to Dublin I didn’t go to the toilet, I didn’t even know there was one on there!”

Starting a new life in London

Joe arrived in London in 1954, after a man who visited Co. Clare on a holiday told him that he could find him a job at a hotel in Ilford, Essex.

When he left Ireland, it was at a time of high unemployment, with the country still recovering from the austerity of World War II and the arctic winter of 1946/47 when people went hungry.

With rationing taking place, and Joe’s uncle sending home flour from America, the opportunity to earn money abroad was an offer that he couldn’t refuse.

He spent four months at what was then called the Beehive Hotel, on Beehive Lane, Ilford, earning £4 a week gardening, stacking shelves and waiting on tables in the evenings, before eventually plying his trade in construction.

But getting to east London wasn’t so straightforward and like the many Irish men and women who treaded the same emigrating footpath, the journey itself was a challenge.

“Once I’d reached Dublin a friend took me for a walk along O’Connell Street,” Joe said. “I’d never been to a city. It could have been Moscow, Beijing, Delhi, anywhere — it was all completely strange.

“I was stood there looking at the lights, I always remember Donnelly sausages. There was a sign illuminated high above the street, to me it was the equivalent of today’s youth going to Disneyland.”

Joe remembers staying there with his friend at a bed and breakfast, in particular the poor night’s sleep he suffered as a result of the unfamiliar sound of traffic passing his window.

Lonely, homesick and exhausted, he next caught the boat from Dublin to Holyhead, before taking a steam train down towards London Euston.

“We boarded an old boat with poor facilities; I mean there were cattle on the boat as well,” he explained.

“The crossing was rough, I’d never been on a boat. I remember we had to sit outside on the deck as there was no room inside, it was cold and the lights went out so we sat in complete darkness.”

The journey may have been a daunting experience, but for many, unlike Joe, scraping up the fares to get out of Ireland was the first hurdle.

He told the story of one Co. Wexford man who cycled 40 miles to Dublin to get the boat, and only managed to afford the ticket to Holyhead and then Birmingham after selling his bicycle once he got there.

And the tale of another who used to borrow a gun from a neighbour every weekend to kill rabbits, most of which he’d sell, with the remainder used to feed his family.

This man also wanted to build a life in London, and in order to gather the funds he’d steal rabbits and pigs’ heads from one butchers, and sell them to another on the opposite side of town.

Life in Ireland before immigration was tough. But it wasn’t much easier once outside.

The tribulations of construction work

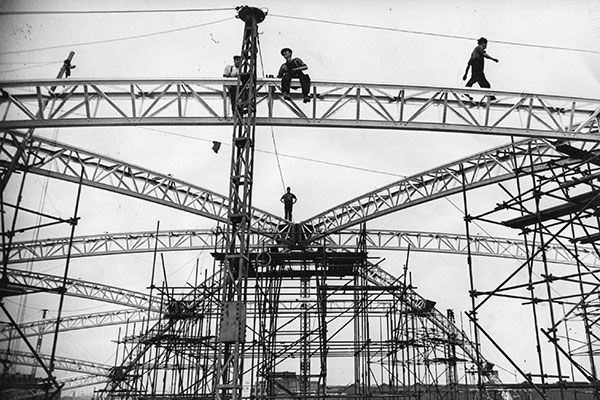

The vast number of Irish men who started life in Britain did so in the world of construction, a dangerous industry for many.

Living conditions weren’t hugely appealing either, with workers required to share rented accommodation, often with no heating. Cookers were communal too, and at a shilling a meter, Joe says that it was often the same people putting money into the gas meter whenever it ran out.

Joe worked for subcontractors up and down the country, from Exeter to Nottingham and Birmingham, for companies including Delacy, Kennedys, Murphy and McNicholas.

Whilst working in Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire, there was an occasion where Joe and his fellow workers had to be rescued by the Fire Brigade by boat in severe flooding.

They had been held up in a farmhouse for two days and two nights, marooned and unable to escape. He emphasised that this was just one example of the conditions that Irish immigrants had to battle during this time.

Some were lucky, able to survive the challenges presented to them. Others weren’t so fortunate.

After his first stint at employment in 1954 at the Beehive Hotel, Joe returned home to Co. Clare for Christmas.

While on the train that was heading to Holyhead, he met a man called Christie Curtain who was heading to Co. Kerry to visit a relative. Like him, he was a construction worker.

But Christie’s fate saw him end up in a wheelchair after he fell off a building on site, injuring his spine. Being in a hospital for a lengthy spell meant he’d missed both of his parents’ funerals.

Several passengers on the train felt sadness at his plight and took pity on him, travelling from carriage to carriage collecting money. Joe never heard about what happened to him after their paths separated at Holyhead.

It’s just one of the many personal stories of those, who, like Joe, found themselves at a crossroads when the time came to make the tough decision to return back to Britain.

There’s light at the end of the tunnel

The world of construction wasn’t always grim. As Joe points out, he rose through the ranks, studying courses that led him from on-site work to Quality Manager and then Audit Manager.

Eventually, he had a company car, a good salary and met his wife, Falkirk native Bridgetta, on St Patrick’s Day in 1960, whom he married two years later and went on to have six children with.

Through occasions of despair for many who emigrated, torn apart from their families, living in harsh conditions and risking their lives in construction, there were glimmers of hope.

As Joe fondly remembers, there were tales of goodwill and generosity.

“I worked for a Tipperary man in London on Eastcote Lane,” he explained. “He told me he’d often heard about Kilburn in London, so he walked from London to Kilburn with no money.

“He went to Sacred Hearts Church on Quex Road and explained his predicament to a clergy member. A priest gave him some money and said he could fix him up with some temporary accommodation.

“He took him to one of his parishioner’s houses where a mother and daughter lived after the husband died. On the first night the man had an eye on the daughter, fell in love and within 12 months he’d had a ring on Rosie.”

Many who emigrated, like Joe, built lives for themselves outside of Ireland and but for holidays, never returned.

Sadly, though, upon setting foot on “home” soil in Co. Clare, as he still refers to it, he no longer identifies the area in which he grew up.

After all, it’s been 60 years since he boarded the bus to Dublin and bid farewell to life, as he knew it.

“Going back there, I don’t recognise anyone,” he said. “Life has completely changed.”