AN ART gallery is not where you’d expect to revel in the work of James Joyce.

Yet here, deep in central London, nestled in a three-floor building not far from the bookshops of Charing Cross Road and the novel readers in Hyde Park, is a veritable feast of one of Dublin’s most famous sons.

We’re on a tour of the free Jumping For Joyce exhibition at the smart Francis Kyle Gallery just off Regent Street in plush Mayfair.

Eponymous curator Francis Kyle is guiding our hand up and down the stairs of the building as we wander in and out of rooms bursting with artistic tributes and works inspired by the author of Ulysses.

“I’ve always liked Joyce and found him fascinating,” Kyle says over a coffee as we pause for a moment of thought. That fact is clear to the naked eye. Over the past two years Kyle’s gallery has amassed more than 100 works which revel in the world of Joyce.

Kyle commissioned the pieces in 2011 after hand-picking 20 visual artists to take part in the exhibition. It’s not the first time he’s asked artists to draw inspiration from the world of literature either.

Over a 35-year career Kyle and his gallery have featured French writer Marcel Proust in past collections, while the gallery has recently tackled TS Eliot’s Four Quartets.

“I think that Joyce is very relevant for today,” says Kyle as we sit around a large array of paintings, some of which depict scenes from James Joyce’s major works, some are portrayals of Dublin life, while others show the writer’s days spent as an exile across Europe in Paris, Zurich and Trieste.

“Our sensibility is formed by him,” he continues, “A lot of people don’t realise [that]. People think Joyce is difficult and inaccessible; they have a go and then they drop it. Or they just look at Finnegans Wake first by mistake.

"They don’t realise that even without reading a word of Joyce, he’s in there. Cinema is influenced by Joyce, the whole nature of it.”

For Kyle, it is Joyce’s humanity that sets him apart from so much art today, which he feels is so abstract in its construction. So how to then go about twinning artists with the form of a novelist? Kyle was, he says, aware of the unique challenge the crossover affords.

“Joyce was a real genius with words. Artists are not word people. It’s not about words,” he says. That said, he had worked with many of the artists before and knew they wouldn’t be limited for inspiration with the Dubliner.

“You can look at the poetry, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Dubliners, there’s enough of Dublin, of Irishness, in all his work,” Kyle says. “Joyce had Ireland in his back pocket – he was always there.”

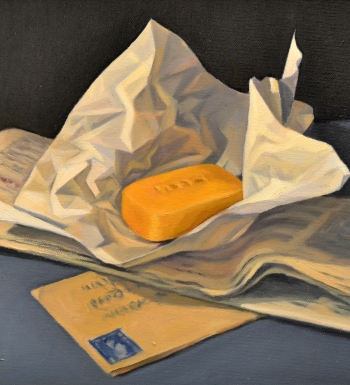

The wine of the country II, by Hugh Buchanan

The wine of the country II, by Hugh BuchananWalking around the exhibition is a real treat. Immediately eye-catching paintings include Philip Hughes’ Dublin, a hand-coloured etching of Dublin’s streets, along with Hugh Buchanan’s The wine of the country II which shows a crushed Guinness can, imprinted in excruciating detail.

Although the majority of the works are paintings, many other forms are employed by the artists.

Michael Marten has shot a triptych of photographs based on Sandycove Beach; Claudia Clare uses ceramic vases to portray a shapely Molly Bloom in various poses; and even animals get a billing through works by both Heather Pocock and a sculpture by Psiché Hughes of Leopold Bloom’s black cat. Something which, on sight, brings to mind the Ulysses scene which is surely the most memorable piece of animal dialogue in literature: “Mrkgnao!”

Steven Hubbard, a materials-based painter, has five works in the show. His pieces are drawn from a range of topics, from The Bar of Soap – which immortalises the lather which Leopold Bloom buys Molly in The Lotus Eaters – to Welcome to the Musee Room, a marquetry work which takes on the author’s most difficult work, Finnegans Wake.

Hubbard confesses to being “slightly daunted” when he was first told that the exhibition would be based around Joyce.

“I did try to read Ulysses when I was about twenty, and it seemed impenetrable to me and I didn’t sit down and try again,” he admits when we speak a few days after the exhibition’s opening night.

Hubbard has been displayed in exhibitions with Kyle for just over a decade, including solo shows. He said he finds the group projects “an education” and particularly stimulating as it offers him an opportunity to re-discover literature he read years before.

On re-reading Ulysses, he said: “It all made perfect sense to me this time, it was fantastic. It’s a fantastic book and brilliantly funny, I thought.”

Hubbard’s decision was to try and channel this humour in two of his works – the mixed-materials work Cork and the oil and marquetry painting Nothing between himself and heaven. And although he may have, like many, struggled with Finnegans Wake, choosing to listen to some parts on CD, he experienced “flashes of clarity” which he worked into his piece.

The Bar of Soap, by Steven Hubbard

The Bar of Soap, by Steven HubbardThe result, Welcome to the Musee Room is an inventive work, with four pillars which rotate in synchronicity held together by bicycle chains. The mixed-media piece was triggered by Joyce’s references to Napoleon and Wellington in Phoenix Park along with quotes from Finnegans Wake: “Mind your hats goan in!” and “Mind your boots goan out”.

Hubbard says he was fascinated by the way some artists had overlapped in their interpretations. This is seen as two Molly Bloom-based works share the name Yes while the soap bar seems to be a recurring motif for many of the artists.

Back in the basement of the gallery, Kyle is showing me a work which depicts Joyce’s Stephen Daedalus and Leopold Bloom urinating against a wall together late at night. The scene, from Ithica, is a work by Anna Wimbledon.

“You look, and you think, ‘I think this guy’s having a pee against the wall’,” chortles Kyle, as he willingly leads me through the entire collection.

He tells me that another work – Towards Merrion Square by Gerald Mynott – marks the meeting spot for a young Joyce who was courting his future wife, the chambermaid Nora Barnacle close to Finn’s Hotel in Dublin.

Peter Milton’s two grandiose works are particularly eye-catching. Tracking Shot nods to Joyce’s contribution to film, using lighting effects which show a younger and an older Joyce meeting in Milan’s Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II.

While The Ministry, a large etching, depicts the famous encounter between Joyce and Marcel Proust in Paris in 1922. The pair met at an enviable dinner-party attended by Stravinsky and Pablo Picasso. The story goes that the Irishman, almost blind by this time – and very inebriated – shared a taxi ride with the French writer.

Proust had for a long time suffered from a chronic lung illness which made him fragile to sudden atmospheric changes. Joyce proceeded to light a cigarette in the cab, to Proust’s horror, before opening the window, which made things even worse. Proust thought Joyce was trying to kill him that evening. The two celebrated writers, not surprisingly, failed to hit it off.

Unmissable in their centre spot of the gallery floor are the aforementioned pottery works, by Claudia Clare, which again show the depth of artistry on display at the exhibition.

Her three pieces, based around the theme Molly’s Odyssey, immortalise Joyce’s female protagonist Molly Bloom who gets the last chapter Penelope and the famous final word of ‘Yes’ in Ulysses.

Clare, a native of Oxford and whose mother’s family hails from Cork and Kerry, first trained as a painter in Camberwell. She only turned to craft ceramics by chance – after keeping a friend company at pottery evening classes. How did she react to Francis’ pick for the project?

“I was pretty ignorant of Joyce,” she admits, adding that she found reading the works tough initially. She did, however, find herself drawn to Molly’s soliloquy after learning through a radio show about the episodic structure of Ulysses.

“I really fell for Molly,” she admits, “because she was so humane, and wonderful. Molly has a robustly feminine sexuality, and she doesn’t hold back on her sexual fantasies.”

There's nothing like a kiss, by Claudia Clare

There's nothing like a kiss, by Claudia ClareSex and sexuality played a role in the creation of Clare’s works. In the same way that Molly Bloom is a muse for the classical character of Penelope, Clare employed “racy romance” fiction writer Rebecca Chance as her muse with Chance’s genre of fiction known as ‘bonk-busters’.

“It’s chick-lit with all the sex left in,” says Clare. “You go in through the bedroom door.”

Clare came up with the idea after attending a book event by Chance at which the novelist was reading a sex scene from one of her books. Afterwards, Clare realised Chance would make the perfect muse for Molly.

“I described Molly’s fantasies as ‘vastly superior filth’, an expression used about Rebecca Chance’s books as well.

“I thought, ‘my God she looks exactly as I imagine Molly looking’ and she’s about the same age, about 45ish, and I thought ‘I can just see Molly, were she not a fictional character, but were she updated to the 21st Century – she would be a consummate writer of bonk-busters’,” laughs Clare.

The reception to the works has been “very strong” Clare says. She attributes this to the collaborative nature of the exhibition, adding that it has “brought a lot of other people in who were not really familiar with Joyce either”.

“It was a very dense and engaging project which I loved. I found it incredibly rich,” she adds. Like Hubbard, Clare has been inspired to read and to explore more of Joyce’s world. It was, she says, “one of the great offshoots of this project”.

Back at the gallery, I’m curious as to whether the process was as collaborative as Clare suggests, that the artists traded initial ideas with each other? Not a bit, Kyle tells me.

“You might think ‘well a collective, they all go off in a run (together)’. No. Artists don’t like to share ideas. They are very secretive, competitive and possessive.

“They define themselves against each other, so, the extent to which each artist has an individual vision is demonstrated by the extent to which they’ll have completely different ways of grasping what looks like the same aspect of the same theme,” explains Francis. “That said,” he smiles, “we have a lot of fun too.”

Jumping for Joyce runs until September 25 at the Francis Kyle Gallery, 9 Maddox Street, Mayfair, London, W1S 2QE. Admission is free.