THE world of traditional music in Britain and Ireland mourned the passing of fiddle player and teacher, Brendan Mulkere, who died in September at the age of 77.

From Crusheen, Co. Clare, Brendan was a huge inspiration to generations of traditional musicians, and a key figure in the development and promotion of Irish music in Britain.

His legacy is huge within music education and Irish traditional music, and his absolute transformative character made an enormous impact in London.

Brendan learned his music from his father Jack, a fiddler and farmer, and his mother, the singer Angela (neé Fogarty).

His main instrument was the fiddle, although he also taught accordion and banjo. Musically, he was influenced and inspired by artists such as Bobby Casey, Paddy Fahey and Seán Maguire, as well, of course, by the prevailing style of Clare fiddling which to some extent has become the dominant style in Ireland and Britain.

Brendan Mulkere moved to London in the early 1970s, teaching in primary and secondary schools, before going into music full-time in 1979.

By then he had already set up Inchecronin Records, which released a number of albums including Memories of Sligo by flute-player Roger Sherlock.

In 1979 he worked on the traditional Irish music programme of the London European City of Culture Festival.

Brendan Mulkere passed away last month

Brendan Mulkere passed away last monthBrendan was a force of nature, always trying to promote Irish music, and indeed Irish culture in general. He founded the London Irish Commission for Culture and Education (1986), and Síol Phadraig, the London Irish Arts Festival (1985) — all the while establishing himself as one of the great tradition bearers and teachers of Irish traditional music.

His friend Kevin Anderson told The Irish Post: “Brendan was a fiddler who organised – an unusual talent. You could hear him in the Thatch Céilí Band, at lock-ins all over, if you knew where to look. Or at the Kilburn Irish Centre if you could stay up late enough and even in Trafalgar Square —presenting Irish music to one and all with a gang of pupils, disciples and joiners-in on St Patrick’s Days.

“Brendan’s Kilburn Irish Centre (Aras na nGael) was the place to hear Irish Traditional music in its purest form. There, circles of Connemara men held hands and sang sean nós and a standing army of Irish and London Irish musicians seldom went home early.

“Brendan organised it all and taught amazingly large classes in ways conservatoires would not have recognised, although might have done well to try to understand.”

Irish traditional music from the 1970s through to the 1990s had to deal with one dark spectre — the shadow of the IRA and its bombing campaign in Britain.

One of Brendan’s festivals was launched the day an IRA bomb went off in the city.

Mr Anderson reflects on this time: “The London Irish lived, and still live, with the fact that Ireland is at the centre of British politics in a way that the politics of other immigrant homelands are not.

“One night a festival car – London Irish Festival written all over it and with four innocent Irish actors on board – was stopped four times between Hammersmith and Willesden by the police. Almost anything London Irish was, apparently, somewhat suspicious.”

Ethnic festivals in the last century were expected to be brief forays into the culture; not for Brendan, however.

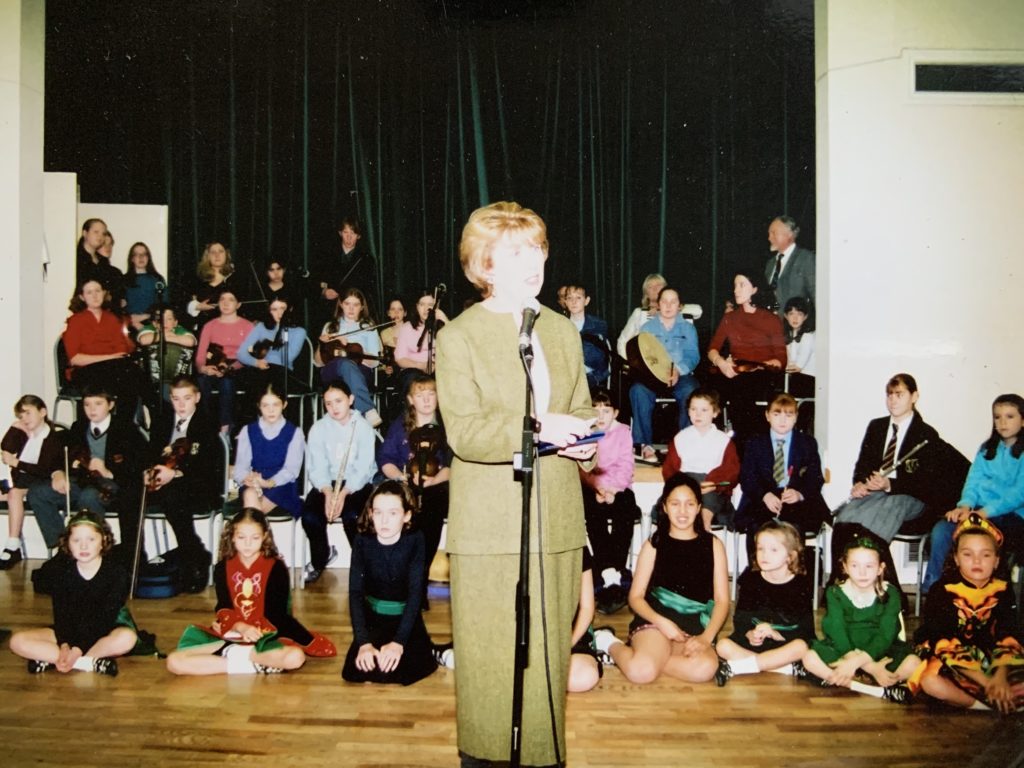

Former Irish president Mary McAleese attends one of Mr Mulkere's lessons

Former Irish president Mary McAleese attends one of Mr Mulkere's lessonsHis were ambitious projects that brought many elements together from traditional music to poetry and theatre.

He promoted productions such as Gabriel Gbadamosi’s No Blacks No Irish, Ray Brennan’s Sidewind about the families of The Birmingham Six, Brendan Kennelly’s Cromwell and Flann O’Brien’s The Poor Mouth.

According to Mr Anderson, “his education projects linked London and Irish schools and piloted classroom materials that encouraged realistic understandings of each culture by the other”.

Brendan returned to Co. Clare in 2015 to play more music, teach more children and to inspire another generation.

He taught at Limerick University and was awarded the Gradam Comaoine (Outstanding Contribution) by TG4, the Irish Language TV station, in 2019.

Brendan is survived by his partner Sharon Coffey and her daughters Claire, Collette and Sinéad Egan, his brothers Des and Enda and sisters Hilda, Florence and Frances.

His partner Sharon told The Irish Post: “Brendan had the unique gift of language, breadth of knowledge, vision and imagination. He was hilarious, intellectual, beautiful. We had a deep connection, admiration and eternal love for each other.”