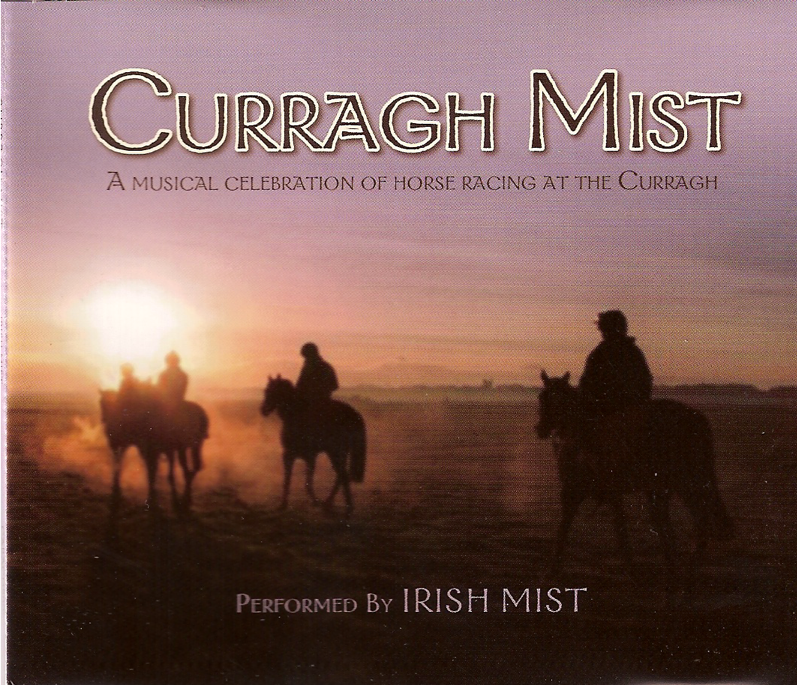

BACK in 2008 I was involved with producing and co-ordinating a song called Curragh Mist written by my late friend, the Cork poet Mary Buckley Clarke.

The song was originally written as a poem before Malcolm Rogers, who writes for The Irish Post and Joe Giltrap, who comes from Kildare, near the Curragh, transformed it into a song and recorded it with their London-based group Irish Mist.

They performed it at the famous Curragh, where it was officially featured on Derby day, so Mary, as a VIP guest, was delighted to hear her song booming out over the majestic stand.

Last May I caught up with my friend Mary for a cup of tea in Clonakilty to talk about Curragh Mist and her other historically inspired songs.

“I wrote [Curragh Mist] first of all as a poem and I was originally going to send it to the Jockey School in the Curragh where they train the jockeys and I did send it to them and they sent it to the Curragh offices,” she explained.

“They got in touch and they said they would love to use it and maybe make it into a song and that’s how that came about and you got involved and produced the record.

When the [planned] refurbishing of the Curragh did not go ahead the song got overlooked,” she added, which was “after we all went up as guests for the Derby Day event, where it was officially launched over the loudspeakers and with a live performance.”

“That was a great day,” she admits.

Cork-born writer and poet Mary Buckley Clarke

Cork-born writer and poet Mary Buckley ClarkeOf course, Mary had written many songs and lots of them had been inspired by history – including her song about The O’Rahilly, The Winding of The Clock.

I asked her where her writing career began.

“Well I’ve been writing all my life really, but the first big thing published was I suppose the article I wrote about Belfast,” she said.

“I had worked in Belfast as a nurse as I did my training at the Mater Hospital in Belfast, which was an independent Catholic hospital run by nuns and of course back then it would very much have been considered as ‘Fenian’ based.

“The Protestant equivalent would have been the Royal Victoria or the City Hospital and this was back in the days of the Troubles,” she explained.

“One day I was going back on duty and I called into a sweetie shop, which was by the Cherry Mount pub nearby and I was buying my sweets when a man said to me “get home”. When I went out it was getting dark and outside were the B specials, who I later found out about, were running around wearing these huge gas masks in and out between the telegraph poles and by the pub and it was terrifying.

“They looked like monsters from another planet, and I was just this young girl from Cork, who knew nothing then about the ‘Troubles’ in Belfast.

“That’s when it all started and the following day the army trucks came down the Falls road and all the people were falling out of the houses and into the backs of lorries.

“Within a couple of weeks of that all the big mills in the Falls Road area were set alight and it was the burning of Belfast, so I wrote an article about that and it was published in the Cork Review magazine and a couple of other places.”

As a nurse Mary would go on to see the devastation wrought by the Troubles in Belfast first-hand.

“Some of my memories are hazy now at this stage but I became part of a war scene really and for some reason all the consultants and doctors, especially the orthopaedic surgeons, seemed to know what weekend there was going to be trouble,” she admitted.

“We came to the point when we had British soldiers living in the nurses’ home on the first floor with submachine guns and they would walk us up and down the road to the hospital to protect us, as we were a Catholic hospital.

“I would lie in bed at night and hear the sound of all the different gunfire and it was quite common to hear explosions. When you went to town cars might get blown up and I was so scared as you did not know where it would come from next.”

Mary Buckley Clarke's poem Curragh Mist was recorded by the Irish band Irish Mist

Mary Buckley Clarke's poem Curragh Mist was recorded by the Irish band Irish MistThe unrest in Belfast would later cause Mary to move to Dublin, where she continued to work as a nurse and also to write.

“I eventually left Belfast and came to Dublin and worked in paediatrics in Crumlin,” she said, “but I had always had a love of writing and I wrote lots of articles for papers like the Cork Examiner, and the poems were the next step really.

“I wrote a poem about Patrick Kavanagh and that was turned into a song The Shoemaker’s Son and that was launched in the Kavanagh Centre and Donal Lunny did the music for that.

“He still plays it at his concerts all over Europe and the song is kind of an answer to Raglan Road.

Mary also wrote a song about New York.

“I wrote my song Angelus on 57th Street for the Milwaukee Irish Music Festival and it came third in that,” she explained, “and then my song The Winding of the Clock came second the following year.

“The 57th Street song was about a guy who has made it in New York, who has made good and he is looking at a picture in an art gallery and what he sees is The Gleaners, the picture by Millet, of women gathering the stray stalks after the harvest and it throws him back to Kerry long ago.”

The song The Winding of The Clock was inspired by the 1916 Rising and The O’Rahilly, Mary recalled the inspiration behind it.

“Well that was The O’Rahilly story and Padraig O’Rahilly was madly enthusiastic for that song.

“He was involved in trying to preserve Moore Street, the area in Dublin where [the Rising ] had happened, at the back of the GPO.

“The O’Rahilly was the first one to actually die as they tried to break out of the GPO - he died in a doorway there.

“He had actually tried to stop the Rising, as he thought it was futile. But it was going ahead anyway and he felt that even though he was against it he had to go. “He had a falling out with Padraig Pearce, so when he got to the GPO Pearce asked him ‘what are you doing here’ and he said “I who wound the clock have come to hear it strike” and that line came from a poem by WB Yeats, and that is where my song came from.”

Michael J McDonagh with long-term friend Mary Buckley Clarke

Michael J McDonagh with long-term friend Mary Buckley ClarkeMary also had the song Breathaway, which Aled Jones went on to play on his BBC show.

“That song Breathaway came from the old poem or one of those philosophical pieces about this guy who met with Jesus as they walked along a beach one day and he said “people always told me that you would help me but when I needed you then you were not there” and he replied “when you were walking on the beach there were two sets of footsteps but if you look behind there was only one set of footsteps as that was when I carried you”.

“So I loosely interpreted that story but sure I have done umpteen others as well like.

The Cork writer also wrote a song about poppies, which was inspired by her husband.

“Well of course none of these songs were written commercially or for money but they come from something deep inside myself,” she admits.

The poppy song Poppy Petals came about because my late husband, who came from London, had served in the British Army in World War Two.

“Terry was a lot older than me and he worked in Reuters but we never heard about Reuters, we always heard about stories from the war and we got so used to listening to him about that, we actually turned off.

“It was becoming to be like the fisherman and the big fish he had caught, it was getting bigger and bigger and he used to exaggerate the stories a bit or maybe he didn’t, I don’t know.

“But he was lucky, as he never shot anybody as he worked as a motorbike courier carrying messages and sometimes he worked as a look out with the big searchlights.

“But even at the very end, when he was in a nursing home with Alzheimer’s and as he got worse and worse and even forgot my name, he never forgot the poppy and it meant so much to him.

“So the Poppy song was written for him really and I placed a poppy in his lapel before his funeral.

Before her death on March 31, aged 73, Mary was still active and had many plans.

Her final words in our chat the previous May outlined just a few of them.

“I’m always writing but have not done so much recently,” she said.

“But I am trying to finish my children’s book about Tigers, as I’d love to have it for my grandson Josh. I have put a lot of research into it and the story is ecologically sound. I must finish it.”

Alas, that was not to be, but her memory and her many songs and those who enjoy them will live on.