JOHNNY McEvoy, from Banagher in Co. Offaly, has a unique place in Irish entertainment.

Neither pure showband, folk, nor country, he occupies a space all of his own, somewhere between all three.

And, unlike many of his contemporaries and those who followed in his footsteps, he has written much of his own material.

In the early days, a lot of this was vaguely seditious: anti-war songs, protest songs—leading to frequent comparisons with Bob Dylan.

Over the years, however, his songwriting developed strongly, and he can lay fair claim to having written some genuine classics: Long Before Your Time (a hit in 1976), Rich Man’s Garden, You Seldom Come to See Me Anymore, and Michael, a tribute to Michael Collins.

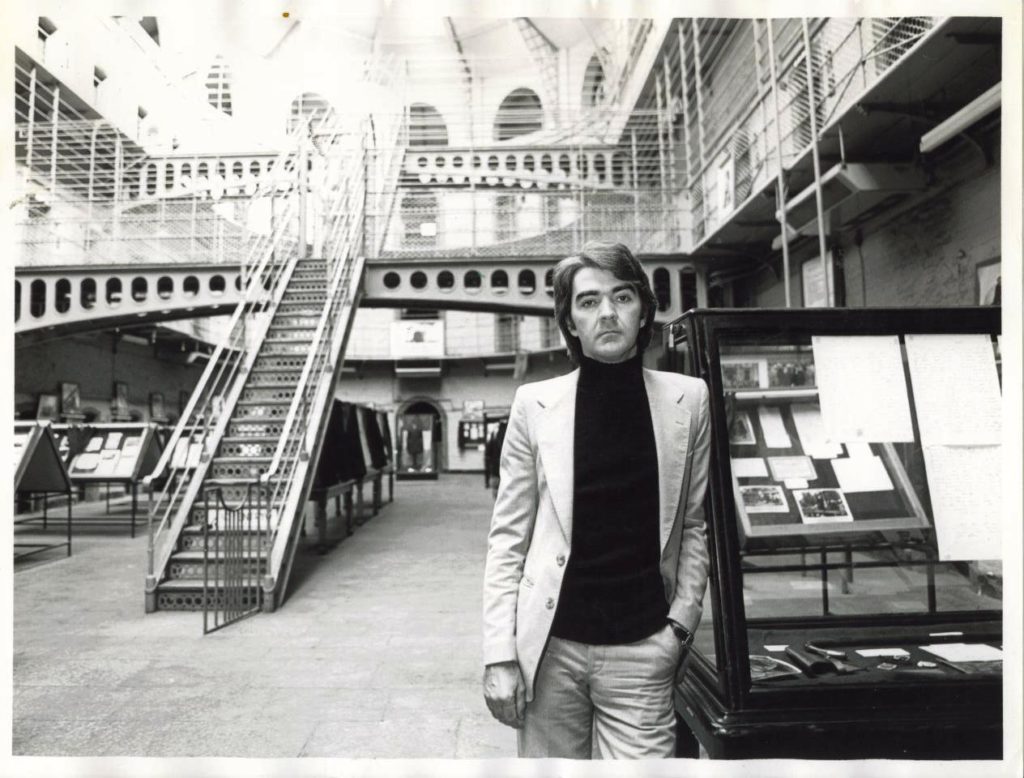

Johnny pictured at Killmainham in 1979 (Pics: Johnny McEvoy)

Johnny pictured at Killmainham in 1979 (Pics: Johnny McEvoy)But it was with a song of unclear origins (see panel) that Johnny scored his first hit.

In 1966, he reached No. 1 in the Irish charts with the definitive version of Mursheen Durkin, instantly turning the song into an essential part of any ballad singer’s repertoire.

The air to which it is sung is Cailíní Deasa Mhuigheo (Pretty Girls of Mayo), a popular reel dating from the 19th century. The lyrics were added, it is believed, in the early 20th century by our old friend Anon. Whatever its origins, the song clicked with the public.

But Mursheen was no overnight success—Johnny had a sackful of Irish ballads over his back.

“From the early sixties I was doing folk clubs and fleadhs. I was brought up on traditional music—I used to spend every summer at my grandmother’s in Co. Galway, and I was virtually fed folk music and storytelling intravenously. It’s one of the abiding memories of my childhood.”

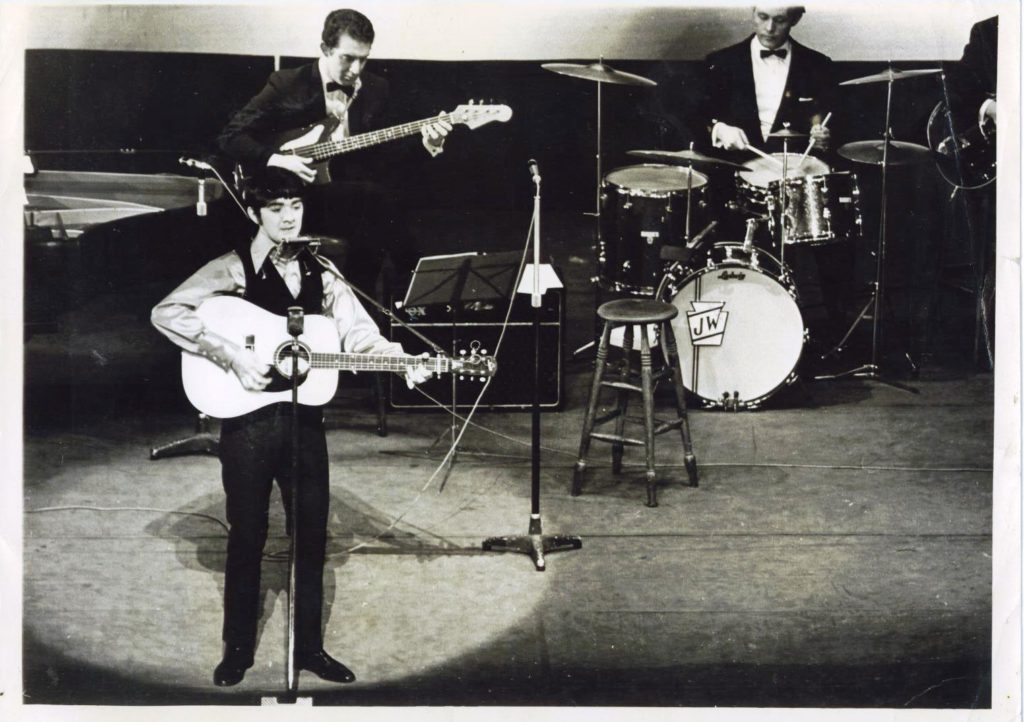

Johnny's Gaiety Show in the 1960s

Johnny's Gaiety Show in the 1960sAs Johnny reached his twenties, he fell under the influence of the wider contemporary folk scene—Hank Williams, Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan. In Ireland, the ballad scene was underway, and The Dubliners and The Clancys were beginning their steady trek to folk superstardom.

It was against this background that Johnny achieved his first hit: “In 1965 I recorded Today Is the Highway—which didn’t do a lot. But the folk boom had begun, and I had a go with Mursheen a year later. It just clicked and sped up the charts. Getting to number one then was about the most exciting thing that had ever happened to me.”

Two further massive hits followed—The Boston Burglar in 1967, and Nora in 1968. Johnny McEvoy was on his way—he soon had his own series on Ulster Television, played the Albert Hall and Carnegie Hall, and toured America, Ireland and Europe.

“They were great days, alright,” Johnny nods appreciatively. “I even did a week at the Gaiety Theatre in Dublin. I was the first singer to try a one-man show—and it was a roaring success.”

With this background—hit records, telly shows, appearances at some of the world’s greatest concert halls, plus an abundance of natural talent in writing, presenting and performing his material—the obvious question has to be asked: why isn’t Johnny McEvoy today an international star of the same order as Christy Moore? Or why doesn’t he sell records by the lorryload like Daniel O’Donnell?

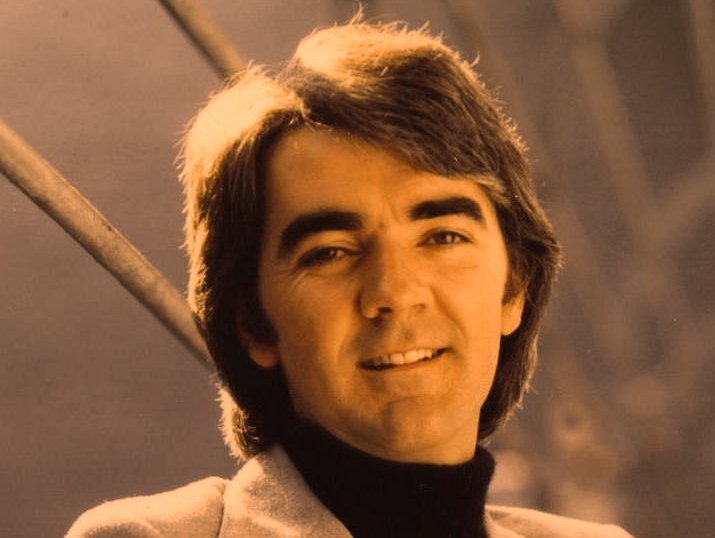

Johnny pictured in 1982

Johnny pictured in 1982Johnny, a thoughtful man, has obviously pondered this question many times before: “Well, paradoxically, it was the demise of the showband that really hit me. Up till then, there was a circuit of venues that could host an act like mine for forty-five minutes or so. But with the end of the showband era, and the closure of a lot of the big ballrooms, that circuit no longer existed. And it was then that I made a big tactical error. Instead of going solo as an out-and-out folk performer, I took the wrong course.

“I formed a country & Irish band and started touring what was left of the old ballrooms. I was never happy in that band—neither the material nor the format really suited me. In a way, I felt I had sold out.”

But Johnny seems totally without rancour.

“Yeah, there were a lot of mistakes. At the end of the sixties there was, as they say, a time and a tide—and I didn’t catch either of them. But I can’t complain. I’ve had decades doing what I love—and I’m not finished yet; not by a long chalk!”

The more lenient hours of the concert circuit mean that Johnny has time to indulge in his hobbies—particularly reading. “I’ve always been especially interested in biographies and history—especially the Second World War and the American Civil War.”

Evidence of this is obvious in his songwriting. His 1977 hit Leaves in the Wind is a poignant anti-war song. “I am a committed pacifist, and have been since my twenties. And I’ve always stayed true to those ideals.”

By the 1970s it looked like Johnny would provide much of the soundtrack for the rest of the century. That he didn’t emulate the likes of The Dubliners or Christy Moore is probably due to a combination of the vagaries of the entertainment business, the fickleness of Madam Luck, and ill-judged career moves. But Johnny remains indomitable.

In 2014, he recorded his first album in over ten years, Basement Sessions 1, and it broke the Top 30 in the album charts. As he said himself, “Not bad for a folky like me.”

The singer pictured in 2020

The singer pictured in 2020He followed that up in 2015 with Basement Sessions 2—second in a series of five studio albums to be recorded and released over a five-year period. Into the Cauldron was his third studio album, with the hit recordings of My Father’s House and Every Night I Dream of Being a Cowboy.

While celebrating 50 years in the business, Johnny became part of Trad Nua's exclusive limited edition The Signature Series, with the first edition of his book My Songs, My Stories, My Life in Music.

In April, Johnny celebrated his 80th birthday and a career spanning 60 years. He has a brand-new album entitled Both Sides—a collection of 14 songs and six audio stories, recorded and read by Johnny. These delve into the things that are important to him.

“I may not always have stayed true to my music,” he concludes, “but I’ve always stayed true to myself.”

Mursheen—a music hall song or folk tradition?

MURSHEEN DURKIN could be a product of the Irish folk tradition — or a relic of the 19th-century music hall.

Like many popular ballads, its history is somewhat murky. Some scholars trace its roots to the stage: a comic music hall song from the 1880s titled Digging for Lumps of Gold, penned by English songwriter Felix McGlennon, shares a strikingly similar storyline — right down to the Irish emigrant heading west in search of riches.

A dispute even arose in 1885 when McGlennon sought damages after the song was performed without permission in a Gravesend music hall, allegedly by Irish comedian Pat Harvey. That version features a character named Corny (or Carney), lending weight to the idea that the stage may have shaped what we now recognise as Muirsheen Durkin.

On the other hand, the tune has been collected and preserved within Irish folk tradition. It appeared in Colm Ó Lochlainn’s More Irish Street Ballads in the 1960s and is often sung to the air of Cailíní deasa Mhuigheo (The Pretty Girls of Mayo), a traditional Irish reel from the 19th century. This gives the song strong roots in oral transmission and suggests it may have evolved as a folk pastiche of existing melodies and emigration themes.