THE CLADDAGH Ring is a world-famous image associated with Ireland – and one of romance.

The two clasped hands holding a heart symbolise loyalty, love and friendship; but the history of where these beautiful rings come from may be one of Ireland’s lesser known stories.

Claddagh, a fishing village in the outskirts of Galway, was a thriving and vibrant community in the 19th century – but one that was very much distinct from the rest of Galway and indeed Ireland.

The untouched, traditional community was a world apart from nearby Galway city – but has left us with one of the most iconic symbols of Ireland in the Claddagh Ring.

This is the story of how the Claddagh people lived and worked, before the village was eventually swallowed up by Galway city 80 years ago.

A curious community, the people of Claddagh defied the rapidly changing culture of the 19th and 20th centuries.

They kept to themselves, married within the village and were unchanging in their peculiar traditions.

“They call every man who does not belong to their community a stranger; even a man from the next parish is a stranger; and it their rule not to intermarry with strangers,” wrote British writer John Leech in 1859.

“They do not go beyond their limitations, but they adhere to them.”

Despite being divided by nothing more than the choppy, fast-paced River Corrib, the Claddagh people could not have been more different from their metropolitan counterparts.

In 1820, there was over 3,000 people living in Claddagh – up by almost 1,000 from just eight years previously.

The entire male population of the village grew up and become fishermen, the only industry of Claddagh. Tillage and livestock are rarities within its boundaries.

Claddagh women, like most women around the world at that time, were homemakers.

It was the village’s location at the mouth of the River Corrib, where it meets the Atlantic Ocean at Galway Bay that made it such a fishing stronghold.

Even the Claddagh men’s names came from their fishing industry - “Paddy the Salmon,” “Paddy the Whale, and so on.

And to this day, the Galway hooker boats are still widely associated with the village.

Though Ireland was under British rule for the 19th century, Claddagh people had their own king to revere.

But unlike in Britain where the throne is handed down from parent to child, the King of Claddagh was elected – and was responsible for ensuring the laws of the Claddagh were kept in place.

Galway has always been a hotspot for the Irish language – but even the fluent Gaeilgóirí in the city struggled to understand the Claddagh people’s undiluted use of the native tongue.

James Hardiman, a librarian at Queen’s College Galway (present day NUI Galway), wrote in 1820: “They rarely speak English, and even their native language, the Irish, they pronounce in a harsh discordant tone, sometimes scarcely intelligible to the town’s-people.”

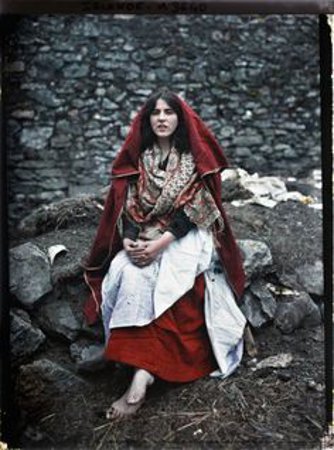

But it was perhaps the clothing that the people of Claddagh wore that really made them stand out from the Galwegians around them.

The brightly dressed woman layered on blue cloaks over their red petticoats – with a brightly coloured head dress to finish it off.

All of their clothes were homemade and Claddagh women stuck to their traditions, wearing these outlandish outfits right up to the demise of the village, when their fashion was completely outdated.

Much like their peculiar traditions, the Claddagh Ring also endured the centuries.

The universally recognisable design became popular outside of the Claddagh village too – where the tradition of passing the ring from mother to daughter continued.

In the end it was an outbreak of tuberculosis that finished off Claddagh.

Despite surviving in their own bubble well into the 20th century, the TB outbreak in 1927 would eventually see Claddagh being consumed into Galway city.

Under fierce protest, the last of the Claddagh people were moved out of their thatched cottages one by one and relocated, when their homes were deemed a health hazard.

The last cottage was demolished in 1934 and since then, the local authorities have rebuilt the village into what is now a residential suburb of Galway city, just across the river from the Spanish Arch.

The unique community may have been swallowed by Galway City – but its legacy is still strong.

The Claddagh Ring is worn by women of Irish heritage right across the world as a symbol of love, friendship and loyalty – and one of the most recognisable Irish images.

As British travel writer H. V. Morton wrote of Claddagh in the village’s dying days in 1930: “The picturesque Ireland will likewise vanish bit by bit, but, like Galway city its real character will not alter.”

The Claddagh Ring

THE Claddagh Ring can be traced back hundreds of years – to at least 1700, during the reign of Mary II in Britain.

Legend has it that a young Irishman, Richard Joyce, was kidnapped by a band of Mediterranean pirates when out at sea.

He was sold by the pirates to a wealthy goldsmith who, over many years of captivity, taught Joyce the skills of his trade – with Joyce becoming an excellent craftsman.

But the goldsmith grew fond of Joyce and despite offering him a hefty financial package and his daughter’s hand in marriage, Joyce opted to go back to his native Claddagh.

Here, he was met by the love of his life, who had waited all those years to lay eyes on him again.

He crafted the Claddagh Ring – made up of interlocking hands to represent friendship, a crown to show their loyalty and a heart to symbolise their never-ending love.

That symbol would be associated with Claddagh for centuries to come.

** Originally Published on: Dec 27, 2015 , by James Mulhall