Farouk Alao’s artistic journey did not begin with a clear plan to become an artist.

Born in Nigeria and raised on the southside of Dublin in Knocklyon, Farouk’s early years were shaped by a feeling of responsibility.

“When I was younger, around 12 or 13, I was trying to figure out how best to support my family in the future,” he says. “I was very proactive in trying to figure that out.”

That sense of purpose guided many of his early decisions.

“I kept landing on things that were very computer science focused or user interface design,” he says.

“When it came time to fill out my forms for university, those were the kind of options that I put down.”

But creativity was never far from reach. “I’ve always loved the arts and creativity,” he says.

As a child, he was fascinated by Egyptology and Aboriginal art.

Fashion was another big influence, shaped by his mother’s work as a seamstress.

“She had her own store in Nigeria, and when we came to Dublin, she was still making stuff for other people. So I was always surrounded by clothes.”

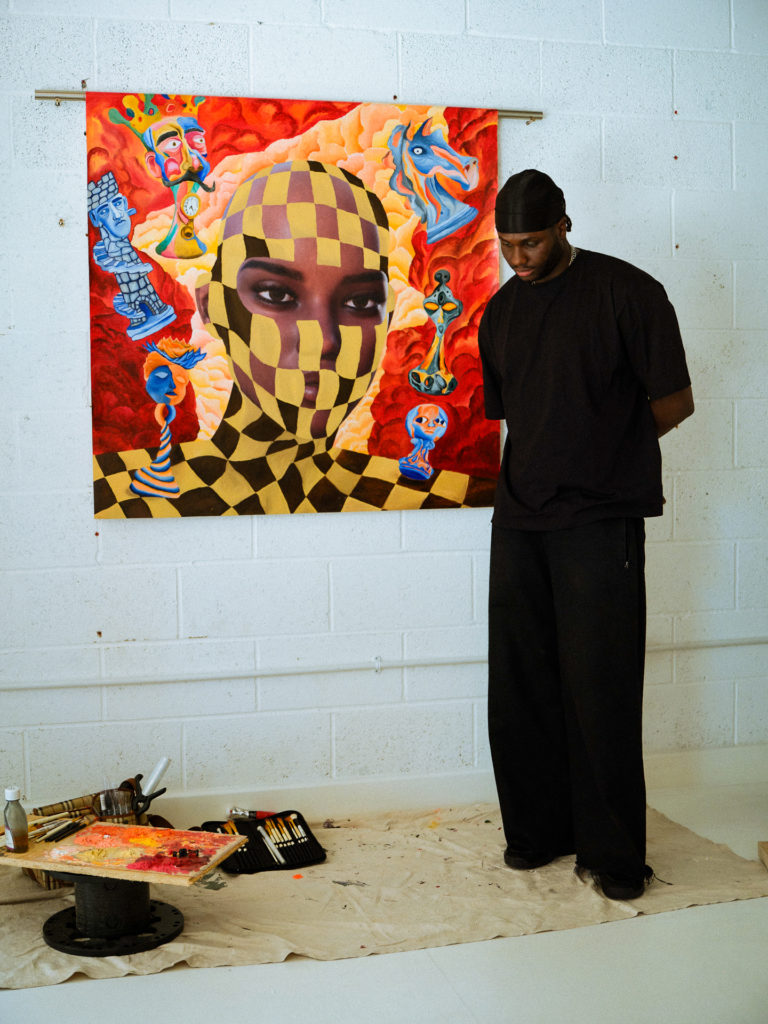

In the studio (Photo by Aaron Farley)

In the studio (Photo by Aaron Farley)Despite this, the formal education system did not come easily. Farouk describes his early schooling as difficult.

When his Leaving Cert results came in, he believed university was no longer an option. “When I got my exam results, they were terrible, and I initially thought I wouldn’t be going to university.”

Then came an unexpected turning point.

Having submitted a portfolio to Limerick School of Art and Design (LSAD), Farouk received an offer that would change the direction of his life.

“They sent me a letter offering me a place,” he says. “Limerick, and particularly the art college itself, is a very open-minded place. It was the first time in schooling that I felt comfortable.”

At LSAD, Farouk found a place that celebrated curiosity.

“It was the first time I was truly surrounded by creativity at that intensity,” he says.

With supportive tutors and a freedom to explore ideas without rigid constraints, he flourished.

“I think that’s what makes me quite creative as well, because I’m so open to going down so many different routes.”

That openness continues to define his practice today.

Farouk works across art, photography, fashion, painting, 3D animation, film and web design.

“For a long time I used to think that I had to figure out what my style is,” he says. “But I’ve learnt over time that if you keep trying, your style just pops up eventually.”

Looking back on his work, certain themes emerge.

“The recurring things are colour intensity and finding different ways to be emotive and present people and stories in an unconventional way,” he says.

His academic interests also inform his work, particularly punk and hip-hop, which formed the basis of his thesis.

Farouk 858 (Photo by Aaron Farley)

Farouk 858 (Photo by Aaron Farley)The number 858 originated from his early experience of dyslexia and ADHD.

Struggling to spell the word “eight”, he devised a mnemonic: “eight five eight”. It became part of his email address, then his social media, and eventually his signature.

“In school I used to get bullied for my name, and being one of the few Black kids in the area, I didn’t always feel comfortable writing it down,” he says.

Signing his work as “Farouk 858” became both a shield and a statement.

While studying and working in Ireland, Farouk began spending summers doing modelling work in London.

Wanting to recreate that vibrancy at home, he began organising exhibitions with friends in Limerick under the name 858.

“It was always part of my Instagram handle, and people just started to know me as Farouk 858,” he says.

“It has evolved so much,” he says. “858 is the clothing brand, Studio 858 is the creative studio, Farouk 858 is me the artist, and then there is 858 Art Club.”

Founded in January 2025, the Art Club was created to help people “learn how to think and create”.

What began with a handful of people now regularly attracts between 30 and 60 participants.

His first major exhibition took place at the Temple Bar Gallery in Dublin, alongside works by Louis le Brocquy and emerging artists.

“For me it was so cool to be in a real gallery, especially one I had been going to for years,” he says.

That exhibition led to further opportunities at both Temple Bar Gallery and the Irish Museum of Modern Art.

“One thing led to the other,” Farouk says. “I’m very grateful to those curators for opening the door. It really helped me believe in myself that I could go down this route.”

Alongside his artistic practice, Farouk also worked on major design projects, including contributing to the rebrand of Limerick city with the local council.

Farouk and his art (Photo by Finn Harney)

Farouk and his art (Photo by Finn Harney)But when he moved to London full-time, he felt the need to rebuild.

“I felt like I had to start from zero,” he says. “I didn’t know how much of the work I had done translated over here.”

Even so, opportunities followed. His exhibition at the Tate came together organically after a conversation with someone involved in Young Tate.

When the call came, the timeline was tight, leaving just a matter of weeks to pull everything together.

“At the time, I don’t think I took in how big a deal it was,” he says. “Sometimes I look back and think, ‘Damn, that really happened.’”

Despite these milestones, Farouk remains grounded. “I treat any job or exhibition with the same level of intensity and care,” he says.

“Those moments are great, but they can be fleeting.”

Ultimately, Farouk’s ambition extends beyond personal success.

“The next thing for me is creating the most significant art company in the world,” he says. For him, that means building a business that allow artists to sustain themselves.

“858 is the engine that enables me to give other creative people the opportunity to get paid for their work.”

At the core of everything is the same motivation that guided him as a teenager in Dublin.

“I still have that same goal,” he says. “To support my family now and my future family. That’s what drives me.”

Though London is now home, Ireland is never far from his mind.

He misses his family, walks in Dún Laoghaire, chicken fillet rolls and, of course, the people.

“I know it’s cliché,” he laughs, “but I really do miss them.”